In 1979, hitchhiking was perfectly safe. Young people, especially in California, thought nothing of sticking out their thumbs along the Pacific Coast Highway or any freeway on-ramp. It was an era of freedom, trust, and believing that the open road was safe.

Then bodies started appearing.

Young men, all thin, all white, completely nude. Signs of strangulation. Rope burns around ankles and wrists. Dumped near freeways across Southern California.

By 1980, the death toll had reached 21. Parents lived in terror. The media dubbed the perpetrator “The Freeway Killer.” And law enforcement had no idea who he was or when he’d strike next.

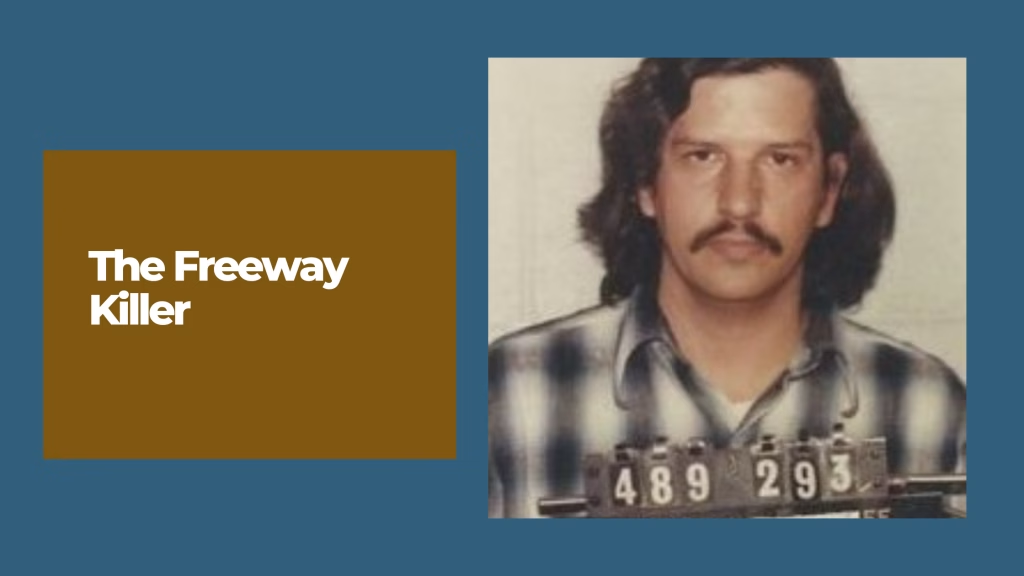

The killer was William Bonin, a 32-year-old truck driver who’d already served time for sexually assaulting four teenagers in 1969. The system had released him in 1978, declaring him “cured.” Just six months later, the murders began.

This is the story of one of California’s most prolific serial killers, a man whose crimes were so horrific that veteran homicide detectives said they turned their stomachs. It’s also the story of confidential interrogation tapes that were never meant to be released, where Bonin calmly describes murders the way someone might discuss a baseball game.

The First Body

Marcus Grabs was a 17-year-old West German exchange student who’d come to the United States with big dreams and little money. He was hitchhiking along the Pacific Coast Highway, hoping to see more of California before heading down through Mexico toward South America.

Someone picked him up. They never made it to Mexico.

Marcus Grabs was discovered stabbed to death in the Topanga Park area north of Malibu. Forensic tests showed he’d been sexually assaulted. His nude body had been dumped in a remote location with no witnesses, no clues, nothing that tipped off who could have done it.

Police wondered: why such a remote location? Why a nude body of a young man?

In the 1970s, law enforcement lacked the forensic technology available today. No DNA testing. Limited computer databases. They needed evidence, but they had almost nothing.

That’s when they contacted different homicide bureaus, asking if any similar sex crimes were being investigated. The answer was yes.

A young man in the San Fernando Valley had disappeared.

Tommy Lundgren: The Boy Selling Flowers

Brenda Axtell always remembered the 1970s as the best time of her life. She and her brother Tommy grew up in the San Fernando Valley, playing baseball in the street with neighborhood kids.

Tommy was a hustler in the best sense of the word, always finding ways to make money. One of his jobs was selling flowers on street corners.

On one evening around 7 PM, Tommy’s mother started acting very strange. Tommy hadn’t come home yet. An hour went by. Another hour. Then the 11 o’clock news came on.

“The body of a young boy was found off Mulholland Highway today, stabbed multiple times and sexually mutilated,” the newscaster reported.

Brenda’s father flew out of his chair. He called the sheriff’s department and asked about it. They asked why he wanted to know. He said, “Because I think it’s my son.”

It was him. Tommy was 13 years old. He was pretty much unrecognizable. You can’t even really explain the devastation it causes.

The Pattern Emerges

In many homicide cases, detectives don’t have all the pieces. But in this case, one of the few things they had to work on was that Marcus Grabs and Tommy Lundgren were found in the very same area. The coroner doing the autopsy noticed that each boy had been sodomized.

Was there a connection?

Five days after Marcus Grabs’ body was found, a third body was discovered in San Bernardino County: Mark Shelton, who’d been dead for maybe a week. The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department contacted the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to see if there was something similar.

Yes, there was. Nude young men, who were sexually molested, were found in remote locations.

That began the sharing of information between different homicide bureaus. The question everyone was asking: was there a serial killer on the loose?

Then came Donald Ray Hayden, 15, of Hollywood. He’d been stabbed to death and sexually molested before being left in a dumpster just north of the Ventura Freeway. The Hayden murder was already being considered the fourth in a series that included three other killings over the past few months.

Reporter Dave Lopez remembered talking to Orange County investigators after the fourth murder. “I think I found out there was some kind of connection to this, only because of the way these kids were being brutally killed, and almost the same scenario.”

The one thing police had in those days was statistics. When this came along, and you started having an influx, an unbelievable rise in these vicious, horrendous murders, they knew something was wrong.

The Torture Methods

By 1980, law enforcement was concerned that there was a serial killer out there. But they didn’t want to confirm it publicly. Wyatt Hart, press information officer for the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, explained the dilemma: “There are some similarities to the cases, yes. Enough to make you think that it’s the work of the same person? Yes, it could be. But you have to be very careful about what you put out.”

The concern was that information released to the press would also be released to the person committing these crimes, which could hamper the investigation.

Still, law enforcement kept recommending that young people not hitchhike. At Marina High School in Huntington Beach and other high schools in Orange County, flyers were distributed. The message was clear: don’t hitchhike.

Investigators were working 16 to 18 hours a day just on this case. As time went on, the series of killings continued to build and build.

Victim after victim. Steven Brillo is cycling to a movie theater. Junior Wear, hitchhiking in Riverside County. By February 1980, there had been 12 young boys, all viciously murdered in the span of nine months.

Seventeen-year-old Frank Dennis Fox. Bodies dumped by the sides of freeways. The media began calling the perpetrator “The Freeway Killer.”

What the public didn’t know yet was how these victims were being tortured.

One victim had an ice pick shoved into his ear almost three and a half inches. These were things you wouldn’t even dream of comprehending. There was a 12-year-old boy on his way to Disneyland.

The 12-Year-Old Going to Disneyland

In the confidential interrogation tapes, William Bonin describes picking up this young boy in chilling detail.

“I started talking to him, and I asked him where he was going, and he said he was going to Disneyland.”

You have to wonder about it, but then you have to think back to what the times were like. Who today would let a 12-year-old boy go to Disneyland by taking the bus by himself? You wouldn’t do it. Back then, it wasn’t that unusual.

Bonin drove the boy to a remote location. “I tied him up. I had sex with him. I put his t-shirt around his neck. That’s when the youngster realized what was happening, and he yelled off three or four times, ‘I won’t tell anybody.'”

The boy started kicking. Bonin strangled him. The victim was beaten, strangled with his own shirt, and his neck crushed with a jack handle. His body was left next to a dumpster in the city of Walnut.

This level of brutality was consistent across all of Bonin’s murders. Dr. Von Capelto, a clinical psychologist who saw Bonin many times in the Los Angeles County men’s jail, later said: “The thing I’m most taken with is he could be talking about the Dodger baseball game. No affect, no remorse.”

Born Into Hell

William Bonin was born in 1947 in Willimantic, Connecticut, a small town where his family struggled with poverty and dysfunction. He had an older brother and a younger brother. Both parents were alcoholics.

When Bonin’s father came home from World War II, he was extremely violent, taking out his fits of anger on his wife and children. A lot of men came home from the war damaged. This had a real effect on the family. He took up gambling and excessive drinking.

The mother, to deal with her husband’s abusive behavior, drank excessively. The kids were almost always dirty and hungry. When Bonin was young, he always dreamed of running away. But he told psychologists he didn’t have any place to run to.

One elementary school friend remembered: “Billy Bonin was in my sixth-grade class. One of his neighbors said the boys would dig up potatoes at night from their gardens and eat them raw and unwashed because they were so hungry. He was smart, but he didn’t talk much to the other kids. Certain kids always made fun of his ill-fitting clothes and shoes. They called him ‘Bugsy Bonin.’ He never fought back, but you could see the hurt in his eyes. Back then, I thought of him as a gentle and very sad soul who never tried to harm anyone.”

Dr. David Foster, a clinical psychiatrist in William Bonin’s appeals trial, found evidence of severe trauma. “William Bonin was subjected at an early age to severe physical abuse by his father. This created frontal lobe damage in his brain. He was also extremely neglected by his mother. This had a profound effect on his developing brain, specifically the connections in the right hemisphere, which impaired his ability to connect socially and emotionally.”

The mother finally concluded she couldn’t handle the three kids. She sent the two older boys, Bonin and his brother Robert, to an orphanage.

At the orphanage, a priest sexually molested Bonin. Later, he was placed in a boys’ correctional home where he was again sexually abused by an older boy.

“What a horrible, tragic thing for this young child,” Foster said. “Already being abused in the orphanage and now being in this boys’ home, and again abused. What chance at life did this little young boy have?”

By age 10, Bonin already had all the risk factors that contribute to creating a serial killer: a cold mother incapable of giving love, physical and sexual abuse, and frontal lobe damage.

From Victim to Predator

When Bonin was 15, the whole family moved from Willimantic to Downey, California. That’s when Bonin changed from being the victim to the perpetrator.

In 1969, at age 22, William Bonin was convicted of sexually abusing four teenagers. The court decided to help him. He was interviewed by psychiatrists who labeled him a “mentally disordered sexual offender” and sent him to Atascadero State Hospital for treatment.

Atascadero was supposed to cure these tendencies toward homosexuality and raping young boys. But the methods used there were primitive and brutal. They used extremely aversive techniques: shocks, electrical convulsive therapy, not as treatment but as punishment.

“They had this ancient notion that if you had a homosexual orientation, you could force someone into a conversion to heterosexuality,” explained Don Cothefter, co-founder of the Gay Community Services Center in Los Angeles. “There are records of gay men as young as 14 being sent there. They could do whatever they wanted. Chemical emasculations. A whole new mental illness was created around us.”

Ultimately, after years of treatment at Atascadero and prison, Bonin was released in late 1978. The psychiatrists said there was still hope for him.

Just six months later, the Freeway Killer serial killings began.

In his diary, Bonin wrote: “From now on, there will not be any more victims left alive.”

The Green Carpet Fiber

By 1980, homicide detectives were being creative with limited forensic tools. They used adhesive tape on different parts of the victims’ bodies to detect any hair or fiber.

On Stephen Wood’s body, they found a green fiber. They compared it to fibers taken off other victims. It was the same.

They took the samples to labs. Analysis revealed the fiber was from a carpet sold specifically for vans. They found the type of carpet, the manufacturer, and where it was sold the most.

This was a big break. Now they knew there was a scientific connection between these cases. They were looking for someone who drove a van with a green carpet.

But nothing was uncovered to point to who that suspect could be.

The Break: A Car Thief Names the Killer

Then, most bizarrely, everything changed.

Billy Pugh was a young juvenile car thief who got caught stealing a car seat. He was in custody, waiting for his case to come up. For some reason, he heard on the radio somebody talking about the Freeway Killer, the nude bodies, the remote locations.

Billy Pugh didn’t like the fact that he got caught. He was willing to make a deal.

He told his counselor: “I think I know who that could be.”

The counselor contacted Detective John St. John, nicknamed “Jigsaw John.” He came out the next day and talked to Billy Pugh.

“I was at a party one time,” Pugh explained. “I left the party, came outside, and the guy offered me a ride. Then he started kind of playing around with me, touching me, which I didn’t like. He started telling me how he liked to kill people, how he liked to molest people.”

Billy Pugh was afraid and wanted to get away. When he got to his house, the guy said, “I’m going to let you go because people saw us together.”

The man’s name was William Bonin.

As soon as Jigsaw John finished the interview, he went back and talked to the task force. They ran the name William Bonin through the rap sheet.

They couldn’t believe what they were reading. One offense after another. All sex crimes. The fact that he’d been sent to Atascadero State Hospital, then to prison, because there wasn’t anything they could do with him at the mental institution.

Now they had a name. Now they could build a case.

Catching Him in the Act

Investigators decided: we’ve got to catch him in the act.

On June 11th, 1980, William Bonin drove to the Hollywood area. The surveillance team follows him. He’s driving up and down, then picks up a young man. There’s some type of transaction. They drive to an isolated area.

After a while, the van starts shaking.

The question for detectives: at what stage should they get out and go look inside to see what’s going on? If they wait too long, that victim could be the next person killed.

They move in. Immediately, they see the victim is tied up, handcuffed, and being sexually molested. The victim is 17 years old.

They arrested William Bonin for lewd and lascivious act on a minor. If the victim had been an adult, they most likely wouldn’t have been able to arrest him.

Inside the van: green shag carpeting in the back, very similar to the fibers found earlier. A cord. Pliers. Carjacking. Tire iron. Blood spatter on the walls. Blood on the floor. In the glove box, newspaper clippings of the Freeway Killer.

Also: no handles on the doors. If you were a victim in that van, there was no way of escaping.

The Accomplices

What made William Bonin unusual as a serial killer was his use of accomplices. Very strange for a serial killer to use another person, because that person could be a witness against you.

But Bonin was smart in the way of knowing how to use and manipulate people. He picked people who weren’t that bright.

Vernon Butts was the main accomplice who did the driving. He testified that Bonin would get in the back of the van and pull the curtain. Butts could hear screaming and sexual activity. He was constantly downplaying his involvement, but detectives realized he was confessing.

This was a big break. They arrested Vernon Butts. He was essential for the prosecution, so they made a deal: if he testified against William Bonin, they wouldn’t seek the death penalty.

He gave names of other accomplices: James Munro, homeless, helped with one killing. Greg Miley could be talked into it and participated a few times. And most surprising: Billy Pugh himself, the one who blew the whistle, had actually helped with at least one murder.

Dr. Von Capelto met all of Bonin’s recruits: “They were all very dependent, passive homosexual young boys who were not very bright. One of them had an IQ of 56, and a normal IQ is 100. Bonin took these boys in, made them his lovers, and then asked them to kill. He corrupted them and made them victims also.”

The Confession to a Reporter

Reporter Dave Lopez got unprecedented access to William Bonin through his attorney, Earl Hansen. Hansen pulled Lopez aside one day and said, “My client saw the interview you did with his mother, and he was very happy with the way you treated her. Here’s my card.” On the back, Hansen wrote: “Permission to talk to Bonin.”

What happened in 1980 would never happen today. There’s no way a reporter on a major case like this would get permission to go to the jail and talk to the defendant.

Lopez visited Bonin three times. On the third meeting, Bonin said, “Are you ready? I’m going to tell you something.”

Then he proceeded to confess, hook, line, and sinker.

“He told me that he had killed 21,” Lopez recalled. “I’m in shock listening to this guy describe how they picked up one kid, put an ice pick in the side of his head. One of his accomplices, Butts, went crazy and stabbed another guy 70 times. He told me about some other kid who squealed and cried and was easy to kill. And then he tells me that, you know, he enjoyed it. Once he started, he couldn’t stop.”

Bonin also said he wanted to avoid the death penalty at all costs.

Lopez walked out stunned. He didn’t know what to do with this blockbuster story. On June 29th, 1981, he went on CBS2 and told the story of how he got the confession.

It was like a bomb had gone off.

The Trial Dilemma

Lopez was under enormous pressure to testify at Bonin’s trial. Prosecution, detectives, police chiefs, investigators, and families of victims all wanted him on the witness stand.

“I was a reporter. I had credibility. And I certainly was a whole lot better witness than the knuckleheads that were with Bonin,” Lopez explained.

But as a journalist, he had sources to protect. California’s Shield Law prevents law enforcement from forcing reporters to reveal confidential information or private notes.

Lopez went to prominent people in the business for advice. One man, Bill Stout, told him: “I know your predicament, but you’ve got to remember something. We are citizens first and journalists second.”

Lopez made his decision. He testified.

“I answered every question and went into detail about what he told me. I testified as a citizen because I firmly believe that when the question comes up, are we journalists or citizens first? We are citizens first. The public has a right to know. The jury has a right to know. Every mother and father who ever loved a child has a right to know.”

He got criticism from many in his profession. But most citizens appreciated that he was very involved in getting this maniac off the streets.

The Verdict

William Bonin was convicted of 10 first-degree murders in Los Angeles County. The jury unanimously determined that the penalty shall be death.

“William Bonin has demonstrated a wanton and total disregard for the sanctity of human life and the dignity of a civilized society,” the judge said.

A few years later, he was convicted of four more murders in Orange County. That jury also agreed on the death penalty.

He was permanently sent to San Quentin, placed on death row, where he remained for 14 years.

His accomplices received lesser sentences. Greg Miley got 25 years to life and was killed in custody in 2016. James Munro got 15 to life and is still in custody. Billy Pugh got six years and is now out.

On February 23rd, 1996, William Bonin was executed by lethal injection at San Quentin State Prison. He was 49 years old.

The Lost Tapes

The confidential interrogation tapes that were never meant to be released provide a chilling glimpse into the mind of a serial killer.

In them, Bonin describes his crimes in a flat, emotionless monotone. When asked why he used an ice pick, he says, “I can’t give you a reason why I used it except for possibly making sure that the person was dead.”

When asked about strangling victims, he explains the technique clinically: “You lay it across his neck, and you apply pressure downward.”

Describing one murder, he says: “I reached down, and I grabbed his nuts, and I squeezed them. And it hurt so he broke loose from the bondage. And that’s why I stabbed him again and again until he was completely sort of helpless. But he was still alive.”

Dr. Von Capelto, listening to the tapes decades later, said: “Clinicians rarely ever have an opportunity to really listen to someone who has killed without any kind of guilt. It’s unbelievable that this was sitting somewhere and never exposed to the light.”

Understanding the Monster

Dr. David Foster, who worked on Bonin’s appeals, believes understanding what made Bonin who he was is crucial for preventing future tragedies.

“Even though William Bonin’s brain did not develop normally and he did not have the capacity for normal affiliation and empathy, he still had this longing for connection. He needed someone who could share his experience, so he went about trying to create those who were victimized like he was victimized.”

Read more: The Donnybrook Killer: Christopher Mhlengwa Zikode

Foster explains that Bonin formed sadomasochistic bonds by being bound, choked, and raped by older boys in the juvenile system. Those he killed? Twelve to 19-year-olds, the same age range as his abusers.

“He explicitly states that what he enjoyed wasn’t the sex. It was about the feeling of control, the feeling of dominance. The worst feeling for a human being is helplessness. All of his life, he’s this helpless victim. When it finally explodes forth, and he has no right hemisphere to evaluate terror, rage, despair, it’s inevitable. There’s nothing that he could do to stop it.”

Foster adds: “It makes me feel compassion for him and sadness and outrage that over and over there were opportunities to intervene in this child’s life. And then we have the tragic loss of all he killed.”

The Victims Who Deserve to Be Remembered

Twenty-one young men lost their lives to William Bonin. They were hitchhikers, exchange students, boys selling flowers on corners, kids taking the bus to Disneyland. They trusted a stranger who offered them a ride.

Some of their names: Marcus Grabs, 17. Tommy Lundgren, 13. Mark Shelton. Donald Ray Hayden, 15. Steven Brillo. Junior Wear. Frank Dennis Fox, 17. Sean King, 14. Stephen Wood. And many others whose families attended every day of the trial, hoping for justice.

Brenda Axtell, Tommy Lundgren’s sister, said: “You can’t even really explain the devastation it causes.”

Dave Lopez, who interviewed many family members, remembers: “You met these people, you met family members, you met the brothers, the sisters, the moms, the dads. I mean, they were just absolutely heartbroken. And you felt so bad because you felt so helpless that you couldn’t do anything. More than once, after I would be finished, I would go home, and my kids were growing up at that time. They were small. I would just look at them and almost have a tear come to my eye, knowing how lucky I am that they’re safe and sound. You count your lucky stars at a time like that.”

Lessons from the Freeway Killer

The William Bonin case teaches us several crucial lessons:

The system failed repeatedly. Bonin was convicted of sexually assaulting four teenagers in 1969. He was sent to Atascadero for treatment using primitive, harmful methods. He was released in 1978, declared “cured.” Six months later, the murders began. He should never have been released.

Early intervention matters. By age 10, Bonin had all the risk factors for becoming a killer: severe abuse, neglect, brain damage, and sexual trauma. There were multiple opportunities to intervene and help this child. None were taken.

Trauma creates trauma. Bonin replicated the type of abuse inflicted on him: bound, choked, and raped. His victims were the same age as those who abused him. Understanding this cycle doesn’t excuse his crimes, but it might help prevent future ones.

Citizens must act. Reporter Dave Lopez made a controversial decision to testify at trial, breaking journalistic norms to help convict a killer. Sometimes being a citizen must come before professional obligations.

Marginalized victims need protection. Many of Bonin’s victims were young gay men or runaways. Their disappearances didn’t initially raise alarms because society had already marginalized them. Every victim deserves equal protection.

Where We Are Now

The death penalty remains controversial. William Bonin spent 14 years on death row before his execution in 1996. Some argue this was justice served. Others point to his horrific childhood and question whether he was beyond all hope of redemption.

Dr. Foster says, “I think as a society, we need to understand what made Bonin who he is, so that we can take both policy actions and individual actions to help prevent these kinds of tragedies from happening again.”

What’s not controversial is this: 21 young men died horrible deaths. Their families never fully recovered. And a system that had multiple opportunities to stop William Bonin before he became the Freeway Killer failed spectacularly.

What aspect of the Freeway Killer case disturbs you most: the system’s failure to keep him imprisoned after 1969, his use of accomplices, or the horrific torture methods he used? Share your thoughts below.

Pingback: Patrick Kearney: The Trash Bag Killer

Pingback: List of serial killers in the United States - Serial Killers Perspectives