Two children were playing by the Leine River in Hanover, Germany, in 1924. They were just minding their business when they stumbled across something horrifying.

A human skull.

At first, police thought it was a prank. Maybe grave robbers. Maybe medical students are weird.

Two weeks later, another skull was found. Same area. Same story. A young male with knife marks in the bone.

Then two more boys found a sack full of human bones near the village of Döhren.

On June 13, two more skulls surfaced. One belonged to a boy who was barely a teenager. One had been scalped.

The city of Hanover officially entered a nightmare. For years, young men and boys had been disappearing. People made excuses: runaways, travelers, the usual explanations.

But now bodies were washing up on shore. Children were finding them.

When police dragged the river, they uncovered 500 human bones and body parts. Knife marks everywhere. Carefully cut joints. Dismembered limbs.

The remains of at least 22 young men between the ages of 15 and 20.

And all the evidence pointed to one man: Fritz Haarmann, a trusted police informant who sold fresh meat at the market.

No one had questioned where that meat came from.

A Troubled Childhood

Friedrich Heinrich Karl Fritz Haarmann was born on October 25, 1879, in Hanover, Germany. His parents were Johanna and Olle Haarmann.

Olle was known as “Sulky Olle” because he was constantly irritable. Always angry. Always off about something.

He married Johanna when he was 34, and she was 41. He didn’t marry her for love. Johanna was well off with money, land, and property. Olle calculated that she’d probably die before him, and he’d inherit everything.

He was in it for the long haul just to get his hands on her assets.

Olle was argumentative and constantly cheated on his wife. His infidelity eventually led to his contracting syphilis. The relationship was toxic, but he stayed with Johanna until she died in 1901.

Just as he’d planned.

The couple had six children. Fritz was the youngest. Olle was a strict authoritarian when it came to punishment, but he barely interacted with his kids otherwise. The only part of parenting Olle enjoyed was disciplining them.

From a young age, Fritz displayed what people called “feminine qualities.” He preferred playing dress-up in his sisters’ clothes and playing with their dolls rather than doing “boy activities.” He enjoyed cooking and sewing, things he learned from his mother.

His father couldn’t stand it.

Olle was terrified his son might be gay. Instead of supporting who his son really was, he mocked him and tried to “toughen him up.”

At school, Fritz struggled academically. Teachers said he was molly-coddled and spoiled. His mother made excuses for his failures instead of helping him. He had to repeat a school year.

Around age 8, something happened that Fritz only spoke about briefly. He claimed a teacher sexually molested him. If true, this horrific betrayal would explain why he emotionally shut down around this age.

The trauma was never addressed. The abuse was never reported.

Military School and Early Crimes

At age 16, Olle sent Fritz to a military academy, hoping to rid his son of his feminine qualities.

Fritz seemed to enjoy military school at first. He was making friends and adapting to the routine.

Then he suddenly collapsed. Doctors diagnosed him with epilepsy. He was dismissed from the academy.

By 1896, Fritz went to work with his father in his cigar factory. It was a job that didn’t interest him. But he tried to keep his father happy.

What his father didn’t know was that Fritz was luring young boys to secluded areas, usually cellars. Once he had them there, he sexually assaulted them.

In June 1896, he was arrested. Due to further offenses, he was sent to a mental institution in Hildesheim in 1897.

When Fritz went to trial, he was deemed “incurably deranged” and unfit to stand trial. He thought he was getting off free.

Instead, he was sent back to the mental institution indefinitely.

The Escape

Six months passed. Fritz grew restless. He didn’t want to be institutionalized anymore.

Unbelievably, he escaped.

Allegedly, his mother Johanna helped him cross the border and flee to Switzerland.

Switzerland wasn’t the picturesque neutral country we imagine today. For Fritz, it was just an easy place to disappear. No one knew him. No one asked questions. He could blend in because no one cared.

Not much is known about what Fritz did in Switzerland. Historians believe he kept a low profile, worked odd jobs, and waited for things to die down back home.

Eventually, his escape and crimes fizzled out of public memory. There was someone else to gossip about.

Fritz returned to Hanover like nothing had happened.

The Charade of Normalcy

When Fritz returned to Hanover, people knew who he was. They knew about his crimes. But he tried to paint himself as reformed, claiming he wanted to live honestly and have a stable life.

He decided to “play house.”

He met a young woman named Erna Loewert. She was respectable. Her family was well-respected. For some reason, she liked him.

Fritz was doing freelance butcher work at the time. He had no real career or prospects. But somehow, he charmed Erna.

They got engaged. For a brief moment, it looked like love might be real. Maybe Fritz really was turning things around.

Then Erna became pregnant. Suddenly, Fritz wasn’t so keen on the relationship anymore.

Luckily for Erna and her unborn child, her family didn’t like Fritz. They dove into his past, found his criminal record, and refused to allow their daughter to marry him.

The engagement was over.

This breakup hit Fritz hard. Not because he wanted responsibility or a child. But because this was the last thread holding his life together. The last thread painted a picture of normalcy.

When that thread snapped, so did he.

A Decade of Crime

For the next decade, Fritz lived his best scumbag life. He dabbled in theft, scams, and break-ins. He had a “try everything once” approach to crime.

Between 1905 and 1913, Fritz was in and out of jail constantly. His crimes were all over the place: larceny, fraud, occasional assault.

At one point, he had a legitimate office job. He tried to convince a female coworker to go grave robbing with him.

By 1913, Fritz was caught for burglary. When police searched his place, they found piles of stolen items linking him to several other break-ins.

He tried to paint himself as innocent. The court wasn’t buying it. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

World War I Changes Everything

World War I kicked off. Germany was low on manpower. Criminals were brought in to work.

Fritz carried out the last bit of his sentence doing manual labor at a manor house. He dug, hauled, and pretended to be reformed. At night, he returned to prison like it was his sad little Airbnb.

When he got out in 1918, he moved to Berlin. Change of scenery, change of pace. But Berlin was too much city, not enough opportunity for scams.

He moved back to Hanover.

Post-World War I Germany was a mess. Poverty, hunger, and black market trading. The whole country ran on desperation and bad decisions.

Fritz thrived. He loved the chaos because it created opportunity. He went right back to hustling stolen goods, hanging around Hanover Central Station like a creep with a pocket watch.

Then came a plot twist that turned this case into true horror.

Fritz Haarmann became a police informant.

The Perfect Cover

Police knew Fritz was a career criminal. They knew his background. But Fritz sweet-talked them into giving him a role as an informant.

He would feed police details about other crooks lurking around Hanover Station. This worked perfectly because by putting others in the firing line, it took the police’s eyes off his own crimes.

Fritz committed to the act. He’d offer to fence stolen goods, then tell police where the goods were. They’d bust his apartment. To keep up appearances, Fritz would even be arrested, acting shocked.

By 1919, Fritz had fully embedded himself in station life. He strutted around like he was law enforcement. He performed citizen’s arrests, busting travelers for fake papers and minor offenses.

Police started trusting him. They relied on him. He built an excellent rapport.

He became their star informant.

This gave Fritz the perfect cover. While everyone thought he was helping clean up Hanover, he was quietly preparing to become one of its most infamous monsters.

The First Victim

In 1918, Fritz’s first known victim was 17-year-old Friedel Rothe. Friedel was a runaway trying to escape his home life. He became friends with a man who loitered around Hanover Central Station.

That man was Fritz Haarmann.

Friedel was last seen with Fritz. When he vanished, his friends and family went to the police. They’d heard about Fritz Haarmann. Could the police check into him?

But Fritz was the police’s best informant. They were unwilling to look. They didn’t want to go to his apartment. They didn’t want to question him. What if they offended him? What if he stopped being their top informant?

They cared more about Fritz’s work than catching a potential monster.

Friedel’s loved ones didn’t stop. They demanded that something be done.

To humor them, police went to Fritz’s apartment in October 1918. They took a very brief look around. They didn’t actually search. Just glanced.

Then they went to Fritz’s bedroom. In his bed was a semi-naked 13-year-old boy.

Police were upset. Not about the child. About having to arrest their best informant.

Fritz was charged and sentenced to only nine months in prison.

Here’s what police didn’t know: Friedel Rothe had already been murdered. His severed head was in that very room, hidden by the stove.

If police had actually searched, they would have found it.

Every victim after this? That blood is on their hands.

Hans Grans Enters the Picture

Fritz avoided serving most of his sentence in 1919. He loitered around train stations, picking up young men, floating around Hanover like nothing happened.

Then he met 18-year-old Hans Grans, a runaway from Berlin who’d fought with his father. Hans was homeless, selling secondhand items at Hanover Station to survive.

Fritz saw him. Hans would become more than a friend. He’d become Fritz’s sidekick, his partner, and eventually one of the most unsettling figures in this case.

Once Hans entered the picture, any scrap of normality Fritz had? Gone.

Shortly after they met, Fritz invited Hans to live with him. They became completely inseparable. Partners in crime in every way.

The dynamic was toxic and dramatic. Hans knew how to manipulate Fritz, mocking him, storming out after fights because he knew Fritz would come begging. It was like Fritz was a lovesick teenager and Hans was the older man.

Eventually, Fritz served his sentence for being caught with the 13-year-old: from March to December 1920. Nine months for being in bed naked with a child.

That’s disgusting.

Somehow, Fritz manipulated the police again. He got back in their good graces and became their top informant once more.

The Killing Ground

Fritz and Hans upgraded their living situation. Through shady connections, Fritz got them a ground-floor apartment in Neuestraße, right next to the Leine River.

Officially, it was for storage. Unofficially, it became one of the most horrifying addresses in Hanover.

From 1923 onward, the streets of Hanover became a hunting ground. Fritz preyed on who he deemed “invisible”: young men who didn’t have anyone looking out for them. Runaways, commuters, boys trying to find work.

The victim list grew and grew.

Fritz Franke, 17, is a talented pianist who dreamed of concert halls. He met Fritz at Hanover Station on February 12, 1923. That night, someone whispered, “He’s not leaving here alive.” The next day, Fritz claimed he’d left for Hamburg. In reality, Fritz Franke’s music was silenced in that room.

Wilhelm Schulz, 17, was only on his way to work when he bumped into Fritz Haarmann. His body was never found. Only his clothes ended up with Haarmann’s landlady.

Roland Huch, 16, told friends he was running away to join the Marines. He never made it out of Hanover.

Hans Sonnenfeld, 19, disappeared soon after. Fritz was later seen wearing his bright yellow coat like a trophy.

In June 1923, Haarmann and Grans moved to a smaller attic apartment. Two weeks later, Ernst Spiecker, just 13, vanished while running an errand for his father. His school cap and braces were found among Haarmann’s things.

Heinrich Struss, 18, and Paul Bronischewski, 17, both disappeared. Their belongings turned up in Haarmann’s possession.

Richard Graff, 17, had told his parents he met a man who promised him a well-paying job. Days later, he went to meet this man and disappeared. Very John Wayne Gacy.

Wilhelm Erdner was lured by a man claiming to be Detective Fritz Harnebrock. That was one of Fritz’s main identities. After this boy disappeared, both Fritz and Hans were seen with his bicycle.

Within days, two more lives were stolen: Hermann Wolff, 15, and Heinz Brinkmann, 13.

The Killings Accelerate

In November, Adolf Hannappel, 17, disappeared from Hanover Station. He was last seen sitting on a trunk before leaving with Fritz and Hans.

Adolf Henies, 19, was looking for work when he vanished in December.

The year 1924 began the same way.

Ernst Spiecker, 17, vanished in January. Ten days later, Heinrich Koch followed. Then Willi Senger, 19, and Hermann Speichert, 16. Both will be gone by February. Both of their belongings were stored neatly in Haarmann’s apartment.

By spring, the disappearances accelerated. Hermann Bock, Alfred Hogrefe, and Wilhelm Apel. All young men. All were last seen at the station.

April 26: Robert Witzel, 18, went to the circus with a man he met at the station. He never came back. Haarmann later admitted he killed him that night and threw his remains in the Leine River.

Two weeks later: Heinz Martin, 14, followed by Fritz Wittig, 17. Hans Grans liked Fritz Wittig’s suit and wanted it for himself. So the boy had to die.

That same day, 10-year-old Friedrich Abeling skipped school. The one day he chose to be rebellious, he crossed paths with monsters. He never made it home.

Less than two weeks later: Friedrich Koch, 16.

Finally, June 14: Erich de Vries, 17. He became the last victim. Days later, his remains were found in a lake near Herrenhausen Gardens, disposed of piece by piece.

The Discovery

In 1924, two children playing by the Leine River found a human skull. Police thought it was a prank or grave robbers.

Two weeks later, another skull. Same area. Knife marks in the bone. Violence at the hands of this.

Two more boys found a sack full of human bones near Döhren.

June 13: Two more skulls surfaced. One from a boy, barely a teenager. One had been scalped.

The city entered nightmare mode. For years, young men had been disappearing. But now bodies were washing up.

Hundreds of locals gathered along the Leine River, searching the banks and the water. More bones kept turning up.

Police dragged the river. They uncovered 500 human bones and body parts. Knife marks everywhere. Carefully cut joints. Dismembered limbs.

A court doctor examined every bone. At least 22 young men between the ages 15 and 20.

Some remains were fresh. Some had been in the water for years.

Suspicion immediately went to Fritz Haarmann. He was infamous among the police. A known predator with a rap sheet going back decades.

But he was also a trusted informant. He drank coffee with officers. He was practically untouchable.

Hanover police called in two detectives from Berlin to watch him.

The Arrest

On June 22, 1924, the two undercover officers watched Hanover Station. They saw Fritz scanning crowds like he was looking for a perfect victim.

Then Fritz started arguing with a 15-year-old boy named Karl Fromm. He demanded police arrest Karl for traveling with fake papers.

Police arrested Karl to see what he knew. Once in custody, Karl told them everything. He’d been living with Fritz for days. During that time, he was subjected to things no child should ever endure.

This was enough to arrest Haarmann.

Police went to his apartment at 2 Rothestraße. Nothing could prepare them for what they found.

The walls, floors, and bedding were completely soaked in blood.

Fritz said, “Oh, don’t mind the blood. That was just me trying to sell illegal meat.”

The detectives weren’t buying it. They questioned neighbors.

Neighbors admitted they’d seen young men coming and going from that apartment. Some witnessed him sneaking out at night, carrying sacks or baskets with heavy items inside.

Those heavy items were body parts.

Nine times out of ten, he was heading toward the river.

Two former tenants admitted they’d followed him one night to the Leine River and watched him dump a sack anda basket into the water.

Police collected all the clothes and personal items from Haarmann’s apartment. Every item was laid out at the station.

Families of missing young men from all over Germany had to come identify what belonged to their sons.

One by one, they did. “That was his jacket.” “That was his shoes.” “That was my son’s keychain.”

Haarmann claimed the items came from his used clothing business.

Bloodstained clothing? Bloodstained jewelry? Nobody was buying it.

On June 29, police connected a set of boots, clothes, and keys to missing boy Robert Witzel. One of the skulls found weeks earlier matched Robert.

Witnesses came forward saying they’d seen Robert at the station with a man dressed as a police officer. That officer was Fritz Haarmann.

When confronted with Robert’s jacket, found with his landlady, the mask finally cracked.

Fritz broke down. His sister had to physically console him.

When she encouraged him to tell the truth, he confessed.

The Confession

Fritz Haarmann confessed to killing, sexually assaulting, and dismembering young men and boys from 1918 to 1924.

He called it a “rabid passion” he couldn’t control. He said he didn’t mean to hurt anyone. It just happened “in the heat of the moment.”

Everything found about his victims told a different story.

Haarmann admitted he would attack during an uncontrollable frenzy. He would strangle them. Then he would do something horrifying.

He would bite into their neck right at the Adam’s apple. He would bite in, break the skin, and tear out their throat with his bare teeth.

Hence the name: The Vampire of Hanover.

Only one person ever escaped this fate. But he was so ashamed he didn’t go to the police.

After each killing, Haarmann disposed of bodies methodically. He said he hated this part, but his obsession was stronger than his disgust.

He would steel himself with coffee. He would cover the victims’ faces. Then he would begin.

Every detail he shared with officers. The last step was always destroying the skull to make the young men unidentifiable.

When police said they found bones of 22 young men, Haarmann seemed smug. He said there were a lot more. Between 50 and 70.

Could he be bragging? Absolutely. But someone like him? It’s believable there were more.

The Trial

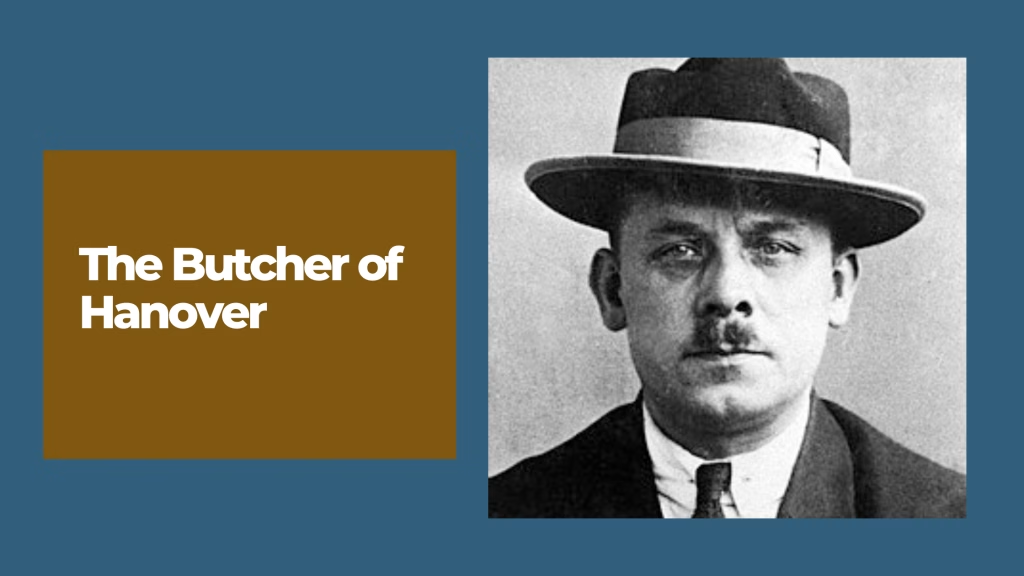

In December 1924, the trial began. It became one of Germany’s first media frenzies.

Every newspaper screamed new nicknames: The Butcher of Hanover. The Vampire of Hanover. The Wolf Man.

Fritz probably loved it. That’s what made him feel powerful.

Inside the courtroom, he was disturbingly calm. He even acted as his own lawyer, admitting to 14 murders outright. He shrugged off the rest, saying, “Charge it to me. That’s fine with me.”

285 bone and skull fragments were entered into evidence alongside the bed he killed young men on and the buckets he used to dispose of remains.

The entire courtroom reeked of decay and disbelief.

Then, even more disturbing facts emerged. Neighbors testified they’d seen him carrying meat he’d clearly packed himself. He would sell it. He would boil it.

One woman told police she’d seen what appeared to be a human mouth in a cooking pot.

The details were so graphic and grotesque that the judge cleared the gallery.

The trial exposed police accountability. They’d trusted this man. Haarmann had been working as an informant the entire time he was murdering. Feeding them tips. Walking through their station halls. Having coffee with them.

All while murdering under their noses.

After just two weeks and nearly 200 witnesses, the verdict came down.

Fritz Haarmann was found guilty of 24 murders and sentenced to death by beheading.

When the sentence was read, he didn’t protest. He didn’t look scared. He smiled.

“I accept the verdict fully and freely. I shall go to the block joyfully and happily.”

His partner, Hans Grans, was also sentenced to death. When his verdict was read, he collapsed.

Later, Hans’s sentence was reduced to 12 years because Fritz wrote a letter from prison saying Hans was innocent. This is absurd. Hans lured many of the victims. He was absolutely guilty.

After 12 years, Hans was free. An absolute monster walking among society again.

The Execution

On April 15, 1925, at 6:00 a.m., Fritz Haarmann met the guillotine inside Hanover Prison.

The night before, he spent his evening smoking cigars and drinking Brazilian coffee.

When guards came, he told them: “I am guilty, gentlemen, but I want to die as a man.”

The blade fell. The Butcher of Hanover was gone.

Remembering the Victims

At least 24 young men and boys died at the hands of Fritz Haarmann:

Friedel Rothe, Fritz Franke, Wilhelm Schulz, Roland Huch, Hans Sonnenfeld, Ernst Spiecker, Heinrich Struss, Paul Bronischewski, Richard Graff, Wilhelm Erdner, Hermann Wolff, Heinz Brinkmann, Adolf Hannappel, Adolf Henies, Ernst Spiecker, Heinrich Koch, Willi Senger, Hermann Speichert, Hermann Bock, Alfred Hogrefe, Wilhelm Apel, Robert Witzel, Heinz Martin, Fritz Wittig, Friedrich Abeling, Friedrich Koch, and Erich de Vries.

They were sons, brothers, friends. They had dreams. They had futures. They deserved to live.

Instead, they met a monster who preyed on the vulnerable in a city that failed to protect them.

The Horrifying Truth

The most disturbing part of this case isn’t just that Fritz Haarmann killed at least 24 young men. It’s that he was a police informant the entire time.

He walked police station halls. He drank coffee with officers. He performed citizen’s arrests. He was trusted.

And all the while, he was selling human flesh at the market.

No one questioned where the meat came from.

Fritz Haarmann fooled an entire city for six years. He lived as a police informant by day and a sadistic killer by night.

The horror he left behind still stains German history.

If you’re interested in more cases about killers who operated with authority, check out these related articles:

- John Wayne Gacy: The Killer Clown Who Fooled Everyone

What aspect of Fritz Haarmann’s case disturbs you most? The police failures? The human flesh being sold? Share your thoughts in the comments below.