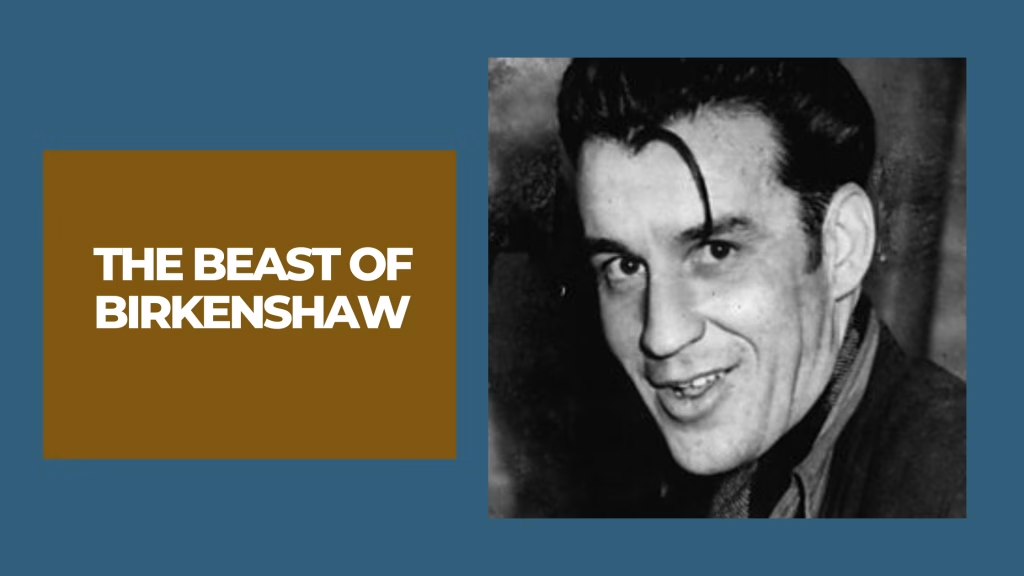

The Glasgow High Court had never seen anything quite like it. A serial killer who’d murdered at least nine people, including young girls and entire families, stood before the judge without a lawyer. Peter Manuel had fired his entire legal team and decided to defend himself against multiple murder charges carrying the death penalty.

And somehow, he was good at it. Disturbingly good.

The judge himself commented on Manuel’s “remarkable skill” as his own lawyer. This wasn’t just any criminal. This was a man who had spent his entire life manipulating people, lying with such conviction that he’d gotten away with rape, and now he stood accused of being one of Scotland’s most prolific serial killers.

But before we understand the monster, we need to understand how he became one.

The American Boy Who Became Scotland’s Nightmare

Peter Thomas Anthony Manuel was born on March 13, 1927, in New York City to Scottish parents Samuel and Bridget. His parents had left Scotland just a year earlier, searching for better opportunities in America. Peter was their second child. Their firstborn, James, had been left behind in Scotland with relatives.

Why leave one child behind? That question haunts the early part of Manuel’s story, but we may never know the answer. Did they plan to bring James over eventually? Or was this always meant to be permanent?

The Manuel family didn’t stay in New York long. They moved to Detroit, Michigan, and then everything changed. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 devastated the American economy. While the Manuels weren’t hit as hard as many families, the financial pressure mounted year after year. Eventually, it became too much.

They couldn’t afford to stay in America anymore.

A Childhood Turned Upside Down

When the Manuels moved back to Scotland, settling in Birkenshaw, Lanarkshire, Peter was about eight or nine years old. Suddenly, this American boy met his older brother James for the first time. Shortly after, his parents had a third child, a daughter.

Think about what that does to a child. Peter had been moving his entire life, crossing entire countries. He’d been an only child, the center of his parents’ attention. Now he was sharing that attention with two siblings, living in a country that wasn’t quite home, with an accent that marked him as different.

The psychological impact must have been enormous. Everything he’d ever known was gone.

Peter did bond with his older brother James, but that relationship would prove to be one of the worst influences in his life. James had grown up differently in Scotland, raised by relatives while his parents were in America. By his early teens, James had developed a mischievous streak that turned criminal. He started with pickpocketing and vandalism, then moved on to theft.

For young Peter, James became a role model. And when you’re ten years old, and your role model is a teenage criminal, you can guess where that leads.

The Bullied Boy Who Stopped Going to School

Peter Manuel was intelligent. Remarkably so. He earned a spot at the local grammar school, a special school for smart kids in the UK. This should have been the beginning of something good.

Instead, it became a nightmare.

The other students bullied Peter relentlessly. He was the different kid, the weird American boy with the strange accent. Kids can be cruel, and they weaponize every difference they can find. To them, Peter’s slightly different way of speaking, his American mannerisms, all of it became ammunition for ridicule.

Peter stopped wanting to go to school. Why would he voluntarily walk into a place where he was ridiculed every single day? He started skipping classes, spending his days with his brother James instead. James was skipping school too, always in trouble, always badly behaved.

The two brothers spent their days together, and Peter began following in James’s footsteps. He started with the same petty crimes, pickpocketing and robbing from stores. The criminal behavior escalated quickly. Soon, he was burgling houses. He even broke into the church right next to his school and stole money from the collection box.

At just twelve years old, Peter Manuel was arrested and sent to juvenile detention. This was meant to be a wake-up call, a stern consequence that would teach him that crime doesn’t pay.

It didn’t work. Nothing ever worked with Peter Manuel.

A Pattern That Never Broke

From age twelve until eighteen, Manuel was in and out of youth detention centers constantly. Whenever he got released, he’d immediately return to crime and get sent right back. His parents tried everything. They moved the family from Scotland to Coventry, England, hoping a change of environment would help.

It didn’t.

In Coventry, Manuel committed one of his most serious crimes yet. He broke into a house in the middle of the night, and when the homeowner’s wife confronted him, he didn’t run. He picked up a large, heavy object and beat her over the head with it. The woman survived, but Manuel was convicted of grievous bodily harm and sent to a youth detention center for an extended sentence.

While there, psychologists gave him assessment after assessment. How could a boy be this consistently criminal, no matter what his circumstances? There had to be something wrong neurologically.

But the tests showed nothing. No mental illness. The only notes mentioned that he might have narcissistic personality traits. He was charming, always the leader, and excellent at persuading people to his side. But he was also a compulsive liar who never took responsibility for anything.

Everyone else was always to blame.

The Injuries That Changed His Brain

During World War II, while Manuel was at a youth detention center in Yorkshire, something happened that may have fundamentally altered who he was. A piece of falling shrapnel from overhead warfare struck him in the head, knocking him unconscious. Doctors believed this left him with some degree of brain damage.

Then came another incident. Manuel and several other young men were working on an electrical task when a faulty wire electrocuted all of them. The shock was so powerful that it killed three of the five. Manuel survived, but with severe memory loss and more suspected brain damage.

We’ve seen this pattern before in serial killer cases. Jerry Brudos, the Shoe Fetish Slayer, suffered a similar severe electrocution at around the same age and went on to become a serial killer. Could there be a connection?

Manuel also had a form of epilepsy that damaged his prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain associated with risk assessment. This explains his willingness to commit crimes knowing he’d get caught. He simply couldn’t weigh pros and cons the way most people do.

Whether these injuries created a killer or just made an existing problem worse, we’ll never know.

The Crimes Escalate to Sexual Violence

When Manuel was finally released at eighteen, he traveled back to Scotland to reunite with his family. That’s when his criminal behavior took a dark turn.

In March 1946, over just one week, Manuel assaulted three different women. The first two he attempted to rape. The third woman, he successfully raped.

This third victim had been riding the same bus as Manuel. He saw her, decided she was the perfect target, and followed her when she got off. Once they reached a quiet alleyway, he attacked, forcing her down onto an embankment where he raped her.

Because this appeared to be a spontaneous attack, Manuel hadn’t covered his face. The woman got a good look at him and gave the police an excellent description. They knew exactly who it was. Peter Manuel was well-known to them by now.

Police brought in the first two victims as well. Both identified Manuel as their attacker. But only the third case had physical evidence, so he could only be charged with one rape. Still, that was enough. At nineteen years old, Peter Manuel was sent to prison for six years.

The Calm Before the Storm

When Manuel got out in his mid-twenties, something surprising happened. He moved to Glasgow and actually built a good life for himself. He got a job as a carpenter, made friends who genuinely liked him (that charm working its magic again), and even got a girlfriend. Eventually, they got engaged.

For a while, it seemed like Peter Manuel had finally turned his life around. Maybe the long prison sentence had finally worked. Maybe he was ready to become a productive member of society.

Then the engagement fell apart due to religious differences. The wedding was called off.

Peter Manuel spiraled.

He developed an obsession with American gangsters like Al Capone and John Dillinger. He thought he was a gangster, too. He’d meet people in bars and pubs, spinning elaborate lies about his criminal exploits, making his petty crimes sound like major heists. He told people he’d fought in World War II and killed people in combat, which was completely false.

You could see it clearly. He’d lost his self-esteem when his relationship ended. He was trying to reinvent himself, to become someone bigger and more intimidating than he actually was.

And then he went back to what he knew best: crime.

The First Murder: Anne Kneilands

On January 2, 1956, seventeen-year-old Anne Kneilands was supposed to go to a dance with a date. He stood her up. But Anne went to the dance anyway, determined not to let a no-show ruin her evening.

On her walk home that night, Peter Manuel spotted her. He followed her, stalking her through the streets until they reached a golf course. There, he attacked her, chasing her across the grass. At some point, she lost a shoe. Police would later find it hundreds of meters from her body.

Manuel beat Anne to death with a large, heavy object. He sexually assaulted her. When her body was discovered the next morning, investigators immediately suspected her date, who’d stood her up. Once he was ruled out, police created a shortlist of known sex offenders and criminals in the area.

Peter Manuel was on that list.

When police brought him in for questioning, they noticed something immediately: Manuel had scratches all over his face. This was just days after the murder, and the scratches were partially healed, as if they’d happened around the time Anne was killed.

How was this not an instant arrest? Looking back, it seems obvious. But Manuel gave them an alibi. He said he was home with his father that night. Police called his father, Samuel, who confirmed the story.

They believed him. They let Manuel go.

Years later, when police finally arrested Manuel for other murders, they arrested his father too. Samuel Manuel had lied to give his son an alibi for murder. Whether he knew what his son had really done that night, we’ll never know.

Something else strange happened after Anne’s murder. Manuel became heavily involved in the case, even after being ruled out as a suspect. He claimed that whoever murdered Anne had stolen items from the construction site where he worked, including boots and a large, heavy object that could have been the murder weapon.

How convenient. It’s almost as if Manuel took the murder weapon from his own workplace.

Police welcomed his involvement, treating him as a witness with valuable information. He gave interviews to multiple newspapers. But every single time, when reporters tried to photograph him, Manuel refused.

“No pictures,” he’d say. “I don’t want any pictures of me in the newspaper.”

At the time, people thought he was just a private person. In retrospect, the reason is glaringly obvious. He didn’t want to be identified.

Three Women Shot in Their Beds

On September 17, 1956, Manuel committed what would become one of his most infamous crimes. He broke into the home of the Watt family in Burnside, just outside Glasgow.

Inside were three women: Marion Watt, her sister Margaret Brown, and Marion’s sixteen-year-old daughter Vivienne. Marion’s husband, William, was away on a fishing trip.

Manuel crept through the house in the middle of the night while everyone slept. He went into Marion’s bedroom first, where she and her sister Margaret were sleeping. He shot both of them in their beds.

Then he went to Vivienne’s room. He sexually assaulted the sixteen-year-old girl, then shot her too.

He stole jewelry and other valuables, then fled into the night.

When police discovered the scene, they immediately focused on one suspect: William Watt, the husband and father who’d been conveniently away on a fishing trip when his entire family was murdered.

For three years, police and the public believed William Watt had murdered his own family. He was arrested, held in a prison cell, and became the most hated man in Scotland. People believed he’d not only killed his wife, sister-in-law, and teenage daughter, but that he’d sexually assaulted his own child.

He was innocent. He knew it, but no one believed him. Imagine the pain of losing your entire family, then being accused of killing them while trying to grieve.

Meanwhile, Peter Manuel was walking free. Police had questioned him as part of their routine check of known criminals in the area, but they’d ruled him out.

What the police didn’t know was that William Watt’s lawyer had been receiving anonymous letters from someone claiming to know who the real killer was. These letters contained details about the crime scene that only the killer would know.

The letters were from Peter Manuel. The actual murderer was writing letters, snitching on himself, giving exclusive information just to torment the only survivor of the massacre.

Why would he do this? He gained nothing from it except the sick satisfaction of stringing along a grieving man whose family he’d murdered. Manuel even met with William Watt in person, sitting across from him in a hotel, describing details about how Vivienne’s clothes had been ripped off.

This was pure sadism. Manuel was doing it for the thrill, for the twisted pleasure of being so close to his victim’s family while everyone looked elsewhere for the killer.

The Murder No One Knew About

In December 1957, Peter Manuel traveled to Newcastle, England, for a job interview. On December 8th, he called for a taxi. When it arrived, driven by 36-year-old Sydney Dunn, Manuel pulled out a gun and shot him in the head.

Why? We don’t know. Police never connected this murder to Manuel until after he was dead, so he never explained his reasoning. Maybe Sydney said something that angered him. Maybe Manuel just felt like killing that day.

After shooting Sydney, Manuel pushed his body onto a different seat, jumped in the driver’s seat, and drove the car to the moors in Northumberland. He dumped Sydney’s body somewhere in those moors and abandoned the car.

The only evidence linking this murder to Manuel was a jacket button. During the struggle or while moving the body, one of Manuel’s buttons popped off. It was found inside Sydney’s car.

Years later, after Manuel’s execution, police found a jacket in his possessions with a missing button. That button matched the one from Sydney’s taxi perfectly.

Some investigators believe Sydney might have been killed by someone else, perhaps a local who knew the best places to hide bodies. There were reports of someone with an Irish accent talking to Sydney that day, and a boat from Ireland had arrived in Newcastle. But the button evidence is compelling.

Whether Peter Manuel killed Sydney Dunn or not, he was never caught or questioned about it during his lifetime. He was free to continue killing.

Isabelle Cooke: The Girl Who Disappeared

On December 28, 1957, just days after Sydney Dunn’s murder, seventeen-year-old Isabelle Cooke disappeared.

She’d gone to a school dance to meet her boyfriend Douglas, who later described her as “the most beautiful girl he’d ever seen, the most beautiful girl in the school.” After the dance, Isabelle started walking home.

She was never seen alive again.

Her disappearance became one of the biggest missing persons cases in 1950s Scotland. Police worked tirelessly, organizing massive manual searches and campaigning for her safe return. Nothing was found except her underwear, which suggested something terrible had happened.

What actually happened was this: Peter Manuel saw Isabelle walking home that night. He stalked her for a while, then, when she turned onto a quiet street, he grabbed her. He took her to an even more isolated location, where he raped her and strangled her to death.

Then he carried her body to a local field, dug a shallow grave less than a foot deep, and buried her.

For weeks, police searched everywhere for Isabelle. Manuel knew exactly where she was, buried in that field, while everyone looked in the wrong places.

Living Among the Dead

Just days later, in the early hours of New Year’s Day 1958, Peter Manuel broke into another home. This time it was the Smart family: Peter Smart, his wife Doris, and their ten-year-old son Michael.

Manuel walked through their bungalow in the middle of the night while they slept. He went from bedroom to bedroom, shooting all three of them in the head. He stole jewelry, checkbooks, and five-pound banknotes that had just been issued by the bank.

But instead of fleeing, Manuel did something that would become the most talked-about aspect of his entire killing spree.

He stayed.

For almost a full week, Peter Manuel lived in the Smart family’s house with their decomposing bodies. He slept in their beds, pushing the corpses aside to make room for himself. He ate their food, used their car to run errands, and even fed their cat salmon once a day, letting it sit on his knee while he stroked it.

He treated the house with respect, keeping it relatively tidy and clean. But the people? He left them rotting where they’d died.

Neighbors noticed odd behavior. The curtains were drawn during the day, which was unusual for the Smart family. The lights were on in the middle of the night. But most people assumed someone was house-sitting while the Smarts were on holiday.

At one point, while driving the Smart family’s stolen car, Manuel spotted a police officer. Instead of avoiding him, Manuel pulled over and offered the officer a lift to work.

Think about that level of arrogance. He’d just murdered an entire family, stolen their car, and was living among their corpses. And he offered a police officer working on murder cases a ride to the police station in that stolen vehicle.

On the way there, they talked about Isabelle Cooke, the missing girl everyone was still searching for. Manuel turned to the officer and said, “Well, I think you’re just looking in all the wrong places for her.”

He knew exactly where she was. He’d put her there.

The Banknotes That Brought Him Down

Peter Manuel’s downfall came from those brand-new five-pound notes he’d stolen from the Smart family. The bank had recorded the serial numbers, and when Manuel started spending them in pubs around Glasgow, someone noticed.

Police tracked the money back to Manuel and decided to move in. They arrived at his parents’ house in Lanarkshire while he was asleep. When officers came inside to arrest him, Manuel begged for five minutes alone. He wanted to explain everything to his parents before they found out by watching him get arrested.

Whether the police granted this wish, we don’t know. But both Peter and his father, Samuel, were arrested that day. Samuel had lied to give his son an alibi for Anne Kneilands’ murder, which made him an accessory to the crime.

When the police put handcuffs on Samuel, Peter Manuel started screaming. He was fine with his own arrest, but seeing his father arrested sent him into a rage. He hurled verbal abuse at the officers.

One officer told him, “We’re going to have to take both of you to the police station.”

Manuel’s response? “You haven’t found anything yet. You can’t take me.”

Eventually, both Manuel and his father voluntarily left with the police. At the station, they were separated into different interview rooms.

And then Peter Manuel surprised everyone by confessing to everything.

The Confessions That Kept Coming

Manuel didn’t just confess to the murders police suspected him of. He confessed to almost double the number of victims they knew about. Some murders had happened in different countries. Some bodies had never been found.

Police were shocked. How could they have had no idea that half of these murders had even taken place?

Manuel took officers to the field where he’d buried Isabelle Cooke. He walked with them for ages, making casual conversation, and at one point, they stopped to talk. Officers asked if he was actually going to take them to the body or just wasting their time.

Manuel looked down and said, “Yeah, I’m standing on her right now.”

His final sick twist. His last day of freedom, and he chose to stand on the shallow grave of one of his victims.

The Trial Where He Defended Himself

But then Manuel did what he’d done before. He retracted everything. He claimed his confessions were false, coerced by police threatening to ruin his family’s lives. He said he was completely innocent.

When his trial began in May 1958 at Glasgow High Court, Peter Manuel made a surprising move. On the first day, he fired his entire legal team and decided to represent himself.

He’d done it once before for a rape charge and gotten acquitted. He thought he could do it again.

For seventeen days, Peter Manuel stood before the court as his own lawyer. He was remarkably good at it. The judge himself commented on Manuel’s skill as a defendant. Even people who knew he was guilty found themselves drawn in by his persuasive arguments.

Manuel argued that all his victims had been murdered by other people. He was just being used as a scapegoat. Most notably, he claimed William Watt had murdered his own family.

He called William Watt to the stand. The man whose family Manuel had murdered had to sit there, having just survived a car crash the week before (he was wheeled in on a stretcher with a neck brace), while his family’s actual killer stood across from him and accused him of the murders.

As if William Watt hadn’t suffered enough.

Manuel also argued that Peter Smart had murdered his own wife and son before killing himself. He had explanations for everything, lies upon lies stacked so high they should have toppled under their own weight.

But the jury saw through him.

Despite his best efforts, Peter Manuel was found guilty of all the murders except Anne Kneilands (due to lack of evidence). He was sentenced to death by hanging.

The End of the Beast of Birkenshaw

On June 11, 1958, just one month after his conviction, Peter Manuel was executed at Barlinnie Prison by executioner Harry Allen.

His final breakfast was an odd choice: fish and chips with a side of tomatoes, a glass of brandy, and a cup of tea.

His last words before the noose went around his neck were: “Turn the radio up and I’ll go quietly.”

It took only about twenty seconds for him to die from the moment he dropped through the trapdoor. He was the third-to-last criminal ever executed in Scotland.

Peter Manuel is buried in an unmarked grave just outside Block D at Barlinnie Prison, where he spent his final days.

After his execution, police found the button evidence linking him to Sydney Dunn’s murder. They also discovered possible connections to over twenty other unsolved disappearances and murders, though none have been definitively confirmed.

If Manuel could keep quiet about Sydney Dunn’s murder his entire life, how many others did he take to his grave?

The Nursery Rhyme Legacy

In a disturbing footnote to this case, Peter Manuel inspired a children’s nursery rhyme in 1960s Scotland. You’ve probably heard “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Well, Scottish children sang a different version:

“Mary had a little cat, she used to call it Daniel. Then she found it killed six mice, and now she calls it Manuel.”

Read more: The Colorado Cannibal: Alferd Packer

Dark humor was how people processed the horror of what had happened in their communities. A man had walked among them, charming and personable on the surface, while secretly being one of Scotland’s most prolific serial killers.

What Made Peter Manuel Kill?

Looking back at Manuel’s life, we can see multiple factors that might have contributed to who he became. The brain injuries from the shrapnel and electrocution. The epilepsy damaged his prefrontal cortex. The possible undiagnosed mental illness.

But many people experience traumatic brain injuries and don’t become serial killers. Many people have epilepsy and live normal, productive lives.

The truth is probably that Peter Manuel was a combination of factors. Nature and nurture are colliding in the worst possible way. A potentially disturbed mind made worse by physical brain damage, raised in an environment where crime became normalized through his brother’s influence, never receiving proper treatment or intervention.

His motives remain unclear even now. He robbed his victims, but never enough to suggest money was his primary goal. He left valuable items behind at crime scenes. Some experts believe he enjoyed the thrill of killing. The fact that he lived among the Smart family’s corpses for nearly a week, that he offered a police officer a ride in a stolen car, that he wrote letters tormenting William Watt, suggest someone who got genuine pleasure from the danger and sadism of it all.

The Beast of Birkenshaw wasn’t just a killer. He was someone who turned murder into entertainment for himself, a sick game where he held all the cards and everyone else was playing blind.

Until those banknotes gave him away, and the game finally ended.

What do you think drove Peter Manuel to kill? Was it the brain damage, an undiagnosed mental illness, or something darker that can’t be explained by science? Share your thoughts in the comments below.