Marina Moskalyova wrote a note before leaving her apartment on June 14, 2006. She scribbled down where she was going, who she was meeting, and even his phone number. Something felt wrong, though she couldn’t explain why.

Her coworker, Alexander Pichushkin, had invited her for a walk in Moscow’s Bitsa Park. He seemed nice enough at work, always quiet and polite. But the news had been talking nonstop about a serial killer operating in that exact park. Over a dozen bodies had been found, all brutally murdered.

Marina decided to be safe rather than sorry. She left the note for her son and headed out to meet Alexander.

She never came home.

That evening, as the sun set over Bitsa Park, Alexander struck Marina in the back of the head with a hammer. He hit her again and again until she was dead. Without a vodka bottle to use as his calling card, he grabbed a stick and shoved it into the wound in her skull. Then he calmly walked away and returned to his family’s apartment as if nothing had happened.

Marina’s son knew something was wrong when his mother didn’t return. He called Alexander, asking where she was. Alexander claimed he hadn’t seen her in months and quickly hung up.

The son called the police. They searched the park and found Marina’s body with the distinctive injuries that marked her as another victim of the Bitsa Park Maniac.

When police reviewed security footage from the Metro station, they spotted Marina boarding a train with Alexander. They had their killer.

On July 16, 2006, a team of riot police burst into Alexander Pichushkin’s apartment and arrested him. His confused mother watched as officers searched their home. They found something chilling: a chessboard with 61 squares marked off, and a diary with dates corresponding to each mark.

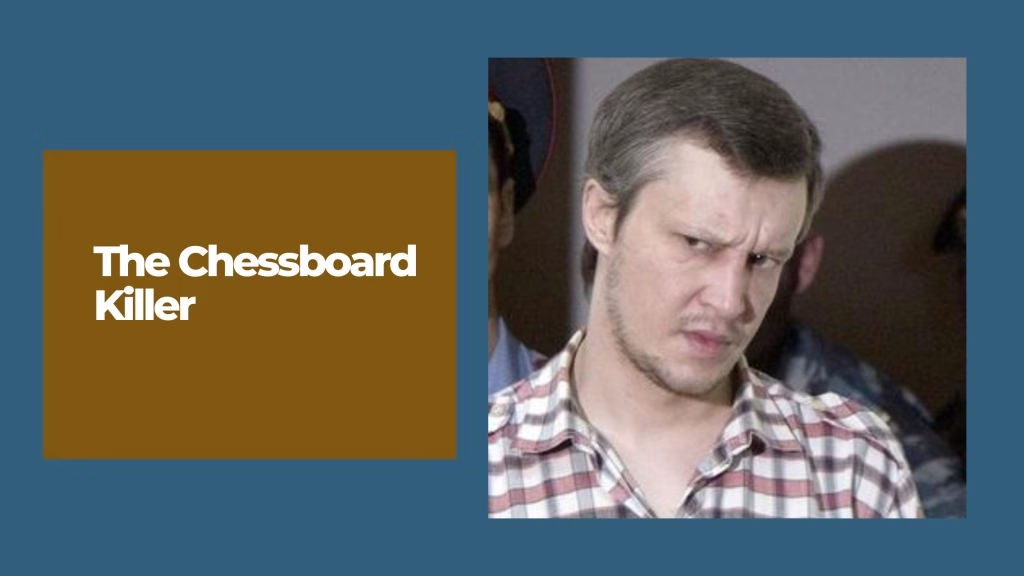

Alexander Pichushkin confessed to killing more than 60 people. He’d marked each victim on his chessboard, treating human lives like pieces in a twisted game. His only regret? He didn’t finish filling all 64 squares before getting caught.

This is the story of the Chessboard Killer, one of Russia’s most prolific serial murderers.

A Normal Boy Until the Accident

Alexander Pichushkin was born on April 9, 1974, in the Cheryomushki district of Moscow. He grew up poor under Soviet rule, living with his mother, Natasha, in a small, cramped apartment in a social housing complex. Locals called their neighborhood “the asshole of the world.”

His father walked out before Alexander turned one. His grandfather stepped in to help raise him alongside his mother.

Despite their tiny apartment, they lived just minutes from the beautiful Bitsa Park. The park covered more than 2,700 acres, with forests, streams, and winding paths. It offered an escape from the concrete surroundings. People came there to relax, ride horses and bikes, and take peaceful walks. Groups of men played chess there, no matter the weather.

Something happened in that park that would change Alexander’s life forever.

As a young child, Alexander was outgoing and easy to get along with. He made friends without trying. But everything changed after an accident on the swings.

He fell off and hit his head hard on the ground. At first, he laughed it off. But as he stood up, the swing came back and struck him on the temple. It didn’t leave an obvious wound, but doctors later determined it damaged his brain, specifically the frontal cortex.

This part of the brain controls emotions and impulses, including the ability to manage dangerous urges. Whether this injury played a role in his future darkness is debatable, but from that day forward, Alexander’s personality completely changed.

The once joyful, outgoing boy became distant and withdrawn. He was prone to fits of anger and became extremely hostile toward everyone. He began acting on darker impulses.

School Became a Nightmare

The injury left Alexander with cognitive issues. Other kids at school bullied him relentlessly, which only fueled his growing anger and resentment. His mother moved him to a special needs school for children with learning disabilities, hoping it would help.

It made things worse. Alexander became even more withdrawn and angry.

As he grew up, Alexander struggled to form relationships with people. He found comfort only in his bonds with animals. This is interesting because many future serial killers show signs of cruelty toward animals in their younger years. Alexander was the opposite.

When his sister Katya was born in 1982, Alexander’s grandfather took on a larger role in his life. He encouraged Alexander to move in with him so he could have his own space. The grandfather tried to be a role model, hoping to steer his troubled grandson in the right direction.

That’s when Alexander discovered chess.

Finding His Place on the Chessboard

Alexander’s grandfather introduced him to chess, and the game changed everything. For the first time in his life, Alexander felt pride. He picked up the game quickly and started beating much older, seasoned players.

Finally, he fit in somewhere. He felt special.

Chess became a way for Alexander to channel his anger and frustration into something constructive. The rush he got from winning, from being seen as exceptional at something, was intoxicating. Even his darker desires for dominance and control felt satisfied by the game.

At least for a while.

When his grandfather died, Alexander fell into severe depression and moved back with his mother and sister. He continued playing chess, but the rush wasn’t the same anymore. Victories felt empty. He started drinking heavily to cope, but the alcohol only made his mental health worse.

His mother tried to help by adopting a dog, knowing how much he loved animals. It barely made a difference. When the dog died, Alexander’s mental health seemed worse than ever.

What nobody knew was that something sinister was growing inside him. Chess had once helped control his darker needs, but now those urges were mixing with his anger and his desire for revenge against the world.

He started threatening children in the park, getting a rush from frightening them. He developed an unhealthy obsession with violent pornography.

When Alexander left school, he had barely any qualifications. The only job he could get was stacking shelves at a local supermarket. He longed for the rush chess once gave him, for people to notice him, to be special.

The Killer Who Inspired Him

In 1992, when Alexander was 18 years old, the trial of serial killer Andrei Chikatilo dominated Russian news. Known as the Rostov Ripper, Chikatilo had murdered 52 people.

Most people who heard the details were horrified. Alexander felt something different.

He lacked compassion for other humans. He saw the Ripper’s crimes as achievements, like winning a game of chess. A game with much bigger stakes.

He became obsessed with the idea that this game would give him the rush he craved. If he could kill even more people than the Ripper, he would be the greatest serial killer Russia had ever seen. He would be special.

His dark thoughts became all-consuming. He needed to kill someone. He needed to know if it would really give him the rush he was seeking.

The First Murder

Alexander had failed to make friends at school or work, but he’d connected with another teenager named Mikhail Odichuk through playing chess in the park. Perhaps out of his own twisted thinking, Alexander believed Mikhail felt the same dark urges he did.

On July 27, 1992, Alexander arranged to meet Mikhail at the park. But instead of playing chess, Alexander told him the plan for the day: they were going to find someone to murder together.

Mikhail thought it was a joke. As they walked deeper into the woods, Alexander grew confused when he realized his friend wasn’t taking him seriously. Alexander felt completely alone with his dark thoughts.

When Mikhail turned his back, Alexander pulled out a hammer and struck him in the back of the head. He hit him more than 20 times until his skull was completely crushed.

Alexander felt a rush like never before. He described it as feeling similar to a first love. This murder was everything he’d dreamed it would be.

But the rush quickly changed to panic when police showed up at his door three days later. They’d discovered the body and knew Mikhail had last been seen with Alexander.

Feeling no guilt or remorse, Alexander found it easy to lie. He denied any involvement or knowledge about what happened to his only friend. With no evidence against him, the police dismissed him as a suspect.

He’d gotten away with murder.

Nine Years of Silence

According to Alexander, he killed two more people that same year. He claimed he pushed a young man named Sergey out of an apartment window because Sergey was dating a neighbor Alexander was obsessed with. He also claimed he later killed that neighbor in the park. Reports on these murders are inconsistent, and it’s unclear if they really happened.

Whatever the truth, Alexander stopped killing after 1992. His “dark passenger” had been satisfied for nearly nine years.

Some people think this pause happened because his idol, the Rostov Ripper, was convicted and executed in 1994. Maybe watching his hero die dampened Alexander’s desire to follow in his footsteps.

For nine years, Alexander worked his boring job at the supermarket and lived in a cramped apartment with his mother and sister. He blended into society as nothing but an ordinary man.

But behind this mask, his dark urges were growing. He began developing a plan to unleash them on the world.

Spending all his free time at the park, he started imagining a chessboard as his canvas. Every square on the board represented a life he could take. If he filled an entire board with victims, there would be no question he’d killed more people than the Ripper.

Everyone would notice him. Everyone would think he was special.

The Killing Spree Begins

On May 17, 2001, Alexander was playing chess with Yevgeny Pronin in the park. After their game, Alexander told him it was the anniversary of his dog’s death. He asked if Yevgeny would come to his dog’s grave in the woods and share a toast to his memory.

Deep in the park, Alexander found the secluded spot where he claimed his dog was buried. He pulled out a bottle of vodka and poured them both drinks. For a while, everything seemed normal as they sat chatting.

Then Yevgeny turned his back on Alexander.

Alexander struck him in the head with the vodka bottle, knocking him unconscious. He dragged Yevgeny’s body to a well in the park, one of several in the area. The well is connected to Moscow’s vast, fast-flowing sewer system.

Alexander pushed Yevgeny down the 30-foot drop into the sewers below. If he somehow survived the fall, Alexander was confident the unconscious man would drown in the water.

Feeling the rush of murder again, Alexander returned home and marked the kill on his chessboard. His dark passenger was now in full control.

Over the next two months, Alexander killed nine more men following the same pattern. He’d invite them into the woods to drink vodka and toast his dead dog. He’d hit them in the head with a hammer or wrench. Then he’d toss their unconscious bodies into the sewers.

Each time, he’d go home and mark another square on his chessboard.

Alexander said, “I would sometimes wake up with the desire to kill and would go to the woods that same day. I like to watch the agony of the victims.”

Nobody noticed any change in his behavior. As far as he could tell, nobody had noticed his victims were missing. Most were homeless men and drifters he knew from playing chess.

If their bodies happened to turn up somewhere, authorities would likely assume they were just drunk homeless people who stumbled, fell into the sewer, hit their heads, and died.

The Victim Who Survived

By February 2002, after killing fifteen people, Alexander was growing tired of his method. While his chessboard was filling up fast, the rush from each kill was getting weaker. Something needed to change.

For his next victim, Alexander selected 19-year-old shop clerk Maria Viricheva. She was three months pregnant. He knew her disappearance wouldn’t go unnoticed like the homeless men, and maybe that would give him the rush he craved.

He couldn’t use his typical promise of alcohol to lure a pregnant woman, so he told her he’d found a stash of black market goods in the woods. If she helped him move them, she could share the goods.

Desperate for money for herself and her baby, Maria agreed.

Deep in the woods, Alexander lifted a manhole cover, claiming the goods were hidden inside. When Maria leaned over to look, he shoved her into the well.

But Maria fought back. She clung to the sides, refusing to go quietly. Alexander pulled her up by her hair and slammed her head against the concrete wall. Dazed, Maria dropped down into the well and disappeared into the darkness.

Alexander walked away, believing he’d just committed his latest murder.

But Maria fought desperately for her life down in the sewer. She struggled to stay above water, her heavy winter clothes making it difficult to swim. She shed whatever she could and tried to keep her head up, determined to survive not just for herself but for her unborn baby.

After hours of swimming, being carried by the current, she found a ladder leading up to another well. Her whole body trembling, her head throbbing, she climbed up. But she was too weak to move the heavy manhole cover more than an inch or two.

She could see a sliver of the world outside. Morning sunlight shone in her eyes. She spotted a terrified woman looking at her, drawn by the moving manhole cover. Before Maria could call for help, the woman fled.

Just as Maria was losing hope, the woman returned with two security guards from a nearby store. The three of them lifted the manhole cover and pulled her to safety.

At the hospital, doctors told her that her unborn child was miraculously unharmed. Maria told a police officer all the details of her attack, including Alexander’s full name.

The officer showed no interest. He dismissed her entire account, apparently because she lacked the right documentation to be living in Moscow.

Had that police officer actually investigated her claims, a serial killer with over a dozen murders could have been stopped. Instead, Alexander was left to walk free.

His crimes were about to get even darker.

A Teenager’s Escape

Believing he’d murdered Maria, Alexander continued killing unchallenged. He took three more lives before selecting 13-year-old Mikhail Lobov as his next victim.

With the promise of cigarettes and vodka, Alexander lured the teenage boy from a Metro station into the park. He struck him on the head with a vodka bottle and dragged him to a well. He shoved Mikhail down into the darkness and walked away, marking another death on his chessboard.

But Alexander had failed to notice that Mikhail’s jacket had caught on a metal piece at the edge of the well. The jacket stopped him from falling in.

When Mikhail regained consciousness, he pulled himself out and ran to a nearby police officer for help.

Just like with Maria’s report, the officer dismissed the boy’s story. He told Mikhail to stop making things up and go home.

One week later, Mikhail ran into Alexander on the street by pure chance. He grabbed a police officer and literally pointed Alexander out as his attempted murderer.

The police still ignored him. They even threatened to arrest Mikhail if he didn’t go away.

If Alexander hadn’t already felt invincible, being pointed out as a killer in front of the police and not even getting questioned must have made him feel truly untouchable.

Growing Bolder and More Reckless

Alexander grew increasingly bold. Rather than targeting homeless people, he turned his attention to his own neighbors. He later claimed that the closer he was to a victim, the better the rush he got from killing them.

One victim was Valeri Klikov, whom Alexander killed because, years earlier, Klikov had said something insulting about his family dog.

Alexander killed more than ten people living in the high-rise buildings in his own neighborhood, including three from his own building. Locals began to notice. These were people with families and friends who were actively looking for them.

Some families followed protocol, waiting the required three days before reporting their loved ones missing. But the authorities, notorious for corruption and indifference, rarely took action.

Their fears grew when yet another neighbor, Constantine Polikarpov, was attacked by Alexander. Alexander hit him three times with a hammer before dumping him in a well.

Constantine somehow survived, but the severe head trauma meant he couldn’t recall any details about who attacked him.

The neighborhood erupted in fear and speculation. Rumors spread that an escaped psychiatric patient from the nearby hospital was hunting people. Some thought the mafia was behind the disappearances.

Despite appeals to the police to find out what was going on, no investigation was launched.

By 2003, Alexander’s chessboard had more than half the squares filled. Yet in some ways, his success at going under the radar robbed him of something he’d always wanted.

Nobody even knew he existed. Nobody cared about what he was doing. In his eyes, he was the most dangerous killer Moscow had ever seen, yet he might as well not exist.

He was growing tired and dissatisfied. It was time for another change.

The Bodies Left in Plain Sight

When Alexander killed again in October 2005, with around 40 lives already claimed, he’d become an entirely different beast. He intended for people to know he existed and to fear him.

When he lured his next victim into the woods with vodka and struck him in the back of the head with his hammer, he didn’t dump the body in a sewer. Instead, he hit him again and again until he’d cracked open the back of his skull.

Then he took the vodka bottle and inserted it into the hole in the head he’d created.

This was going to be his calling card. He left the mutilated body out in the open to be found.

On October 15, police officers patrolling the park stumbled across the body face down with the vodka bottle sticking out of his skull. They had no doubts this was the work of a maniac.

By Christmas, seven more bodies had been found, including a retired police officer named Nikolai Zakharchenko. None of the victims appeared to have been robbed, but they all shared one horrific feature: severe head injuries with vodka bottles or wooden sticks jammed into their skulls.

The media dubbed the killer the Bitsa Park Maniac and compared his crimes to those of the Rostov Ripper. Suddenly, there was immense pressure to figure out who was responsible.

Had Alexander stuck to his usual method of disposing of bodies in sewers, he might never have been caught. But he would never have had the recognition he longed for.

He was so desperate for acknowledgment that he almost revealed his identity to his sister one evening. When she asked who the maniac on the news could be, he fought hard not to blurt out that it was him.

The Investigation Finally Gets Serious

The case was now being handled by Moscow’s elite murder squad. Senior investigator Andrei Suprunenko was put in charge. Finally, someone with experience tracking serial killers was hunting for Alexander.

Suprunenko called in one of Russia’s most experienced forensic scientists, Professor Vladimir Voronov, to study the bodies and crime scenes. But there was very little to go on. There were never any fingerprints or DNA at the murder scenes. The areas where bodies were left were so remote that there were never any witnesses.

As far as the police could tell, none of the victims had any connection to one another. All they could determine from autopsies was that the murder weapon was most likely a hammer.

Read more: The Monster of Toleni: Bulelani Mabhayi

With no concrete leads, 200 police officers were deployed, both in uniform and plain clothes, to comb through the park around the clock. They talked to everyone they could and put together sketches of possible suspects.

They even arrested a man carrying a hammer in his bag, but after 24 hours of questioning, his alibi checked out, and they released him.

Despite all the police attention and media coverage, with many people actively avoiding Bitsa Park, Alexander continued his killing spree. Two women were among his next victims.

In total, authorities discovered twelve bodies, each having suffered the same types of injuries. It was the thirteenth body they found that finally led them to Alexander.

The Murder That Ended Everything

For reasons unknown, Alexander picked his coworker Marina Moskalyova as his next victim. Not only was she someone with direct links to him, but he was fully aware she’d told her son she was meeting him.

It seems impossible to imagine that Alexander expected any outcome other than getting caught when he left Marina’s body in the park on July 14, 2006.

Maybe the added risk gave him an even greater rush. Maybe he found pleasure in the idea that he would finally be identified and acknowledged as Russia’s most prolific serial killer.

When police found Marina’s body, they discovered a Metro ticket in her pocket. They reviewed surveillance footage and quickly found video of Marina with Alexander boarding a train and getting off near Bitsa Park.

With this evidence and Marina’s note, the police headed to Alexander’s home.

His mother, Natasha, answered the door to a swarm of riot police. They told her they were taking her son in for questioning. Alexander showed no signs of resisting as they arrested him and escorted him out.

Natasha was confused until officers handed her a document detailing the murder charges against him. She fell into the couch, trying to comprehend if her son could really be the Bitsa Park Maniac she’d been hearing about on the news.

As police searched the apartment, they found the chessboard with 61 squares marked off. They also found his diary with dates corresponding to every mark.

At the time, it didn’t seem significant. Not yet.

The Confessions That Shocked Russia

In custody, Alexander initially stayed silent. But Detective Suprunenko knew how to push his buttons. He knew Alexander was desperate for attention and admiration.

Suprunenko said, “I told him I admired him, and he liked that. And then he opened up. It was very important for Pichushkin that people think he was a hero, so I made him feel like a hero.”

The plan worked almost immediately. Alexander confessed to the thirteen Bitsa Park Maniac murders; police were already confident he’d committed them. He offered details only the killer could know.

Then he shocked them. He said those thirteen murders were by no means the only ones he’d committed. He’d killed more than 60 people.

Every mark on the chessboard they’d found in his apartment represented one of his victims.

Detective Suprunenko and his team initially thought Alexander was lying to cement his legacy as Russia’s most prolific serial killer. But Alexander provided a chilling level of detail for all the murders he claimed to have committed.

Could he really have killed that many people?

Over the next few months, detectives gathered enough evidence to prove that at least 49 of the murders Alexander claimed were real and happened exactly as he said. They also confirmed three cases of attempted murder, including two victims Alexander had marked on his board without realizing they’d survived.

Russia had indeed caught one of its most prolific serial killers, who’d carried out some of the most brutal crimes the nation had ever seen.

Cold and lacking any sense of remorse, Alexander later remarked that he was happy he’d at least managed to outdo his idol, the Rostov Ripper, by surpassing his body count. But he was disappointed he’d failed to achieve his main goal: to kill 64 people, one for every space on his chessboard.

Describing why he did what he did, Alexander said, “For me, life without murder is like life without food for you. I felt like the father of all these people since it was me who opened the door for them to another world.”

The Trial in a Glass Cage

On September 13, 2007, Alexander Pichushkin stood trial in Moscow. Like his infamous idol, the Rostov Ripper, he was held in a glass cage throughout the entire proceedings.

Many psychiatric experts testified that Alexander was mentally sound to stand trial. They all highlighted that he seemed to have a complete lack of empathy and appeared to relish the power he’d felt both from the killings and the attention he was now receiving.

Throughout the trial, Alexander insisted he should be charged with a minimum of 63 murders, not 49. He even stated that if he’d been able to fill his chessboard, he had no doubts he would have continued killing indefinitely.

Instead of asking for mercy, Alexander taunted the court. He said, “For 500 days I have been under arrest, and for all this time you have all decided my fate. At one time, I alone decided the fate of 60 people. I alone was the judge and prosecutor, and executioner. I was God. I alone fulfilled all of your functions.”

Alexander even fired one of his lawyers in the middle of the trial, accusing him of supporting the prosecution’s case. He was later quoted as saying about the lawyer, “I would cut him open like a fish. I would have killed him like an insect, and I would have received much pleasure from the process. I would cut him up and make belts out of his flesh.”

Coworkers from the supermarket testified that he’d always seemed polite and hardworking. In response, Alexander snapped at them from his glass cage, saying, “Why are you studying me so thoroughly?”

Life in an Arctic Prison

On October 24, after a short deliberation, the jury found Alexander guilty of all 49 counts of murder and three counts of attempted murder.

The judge sentenced him to life in a maximum security prison. His first 15 years would be spent in solitary confinement.

When the judge asked if he understood his sentence, Alexander simply replied, “I’m not deaf.”

The courtroom was filled with reporters and relatives of his victims. Many felt a life sentence wasn’t enough. The mother of one victim stated he should have been given a death sentence. Another family member said he should be handed over to the public for punishment rather than allowed to live in prison at taxpayer expense.

His case reignited debate in Russia about reinstating the death penalty so he could be executed.

A week later, his lawyers filed an appeal for a reduced sentence of 25 years. Their appeal was denied at a hearing where loved ones of his victims screamed and shouted at him in anger and despair.

Alexander’s mother, reflecting on her son’s actions, later said in an interview, “I know now that I raised my son very poorly. I can’t say what I did wrong. I just tried to raise him like a normal mother. I think I didn’t know my son very well.”

As of 2017, Alexander is serving his sentence in an Arctic penal colony known as Polar Owl. During his confinement, he began a relationship with a woman called Natalya and got engaged to her in 2016.

According to reports, Natalya has stated she’s proud of him. Despite never having actually met him in person, she’s determined to marry him and have a child with him. She even has a tattoo of his face with a chessboard on her arm.

The Legacy of the Chessboard Killer

In 2020, another serial killer named Anatoly Slivko was arrested after he murdered six people in 17 days with a hammer. Police said he was attempting to emulate and outdo Alexander’s notorious crimes, just like Alexander had once tried to outdo the Rostov Ripper.

Despite his goal of killing more people than the Rostov Ripper, only 49 of Alexander’s murders were officially confirmed. The Ripper had 52 confirmed kills. Technically, Alexander fell short.

Whatever the true motive for his actions, whether it was his childhood brain injury, mental illness, or just being a twisted individual, Alexander Pichushkin will officially go down in history as one of Russia’s worst serial killers.

Detective Suprunenko, who spent months interviewing Alexander, found one thing most compelling about him. Despite being connected to so many murders, Alexander seemed so ordinary. He had no strong opinions, no real preferences, and offered no particularly deep thoughts about anything at all.

He didn’t seem like a crazed maniac. Just a boring supermarket employee.

But behind that ordinary mask lived a monster who treated human lives like pieces in a chess game. He marked each victim on his board, savoring the power and control he felt with every kill.

When he finally dies in prison, there won’t be many people mourning his loss.

The Chessboard Killer’s game is over. The board will never be completed. And that’s exactly how it should be.

What do you think drove Alexander Pichushkin to kill? Was it the childhood brain injury, his obsession with the Rostov Ripper, or something darker we can’t fully understand? Share your thoughts in the comments below.