On November 17, 1974, a Vietnam War veteran named David Clark was walking down a rural road in Georgia when he spotted something that made his blood run cold. The man emerging from a nearby farmhouse, gun in hand, was unmistakable. His face had been plastered across every news channel and newspaper for weeks.

It was Paul John Knowles, America’s most wanted man.

Clark didn’t hesitate. When Knowles raised his stolen gun and pulled the trigger, nothing happened. The weapon jammed. In that split second, Clark drew his own pistol and turned the tables on one of the most dangerous serial killers in American history.

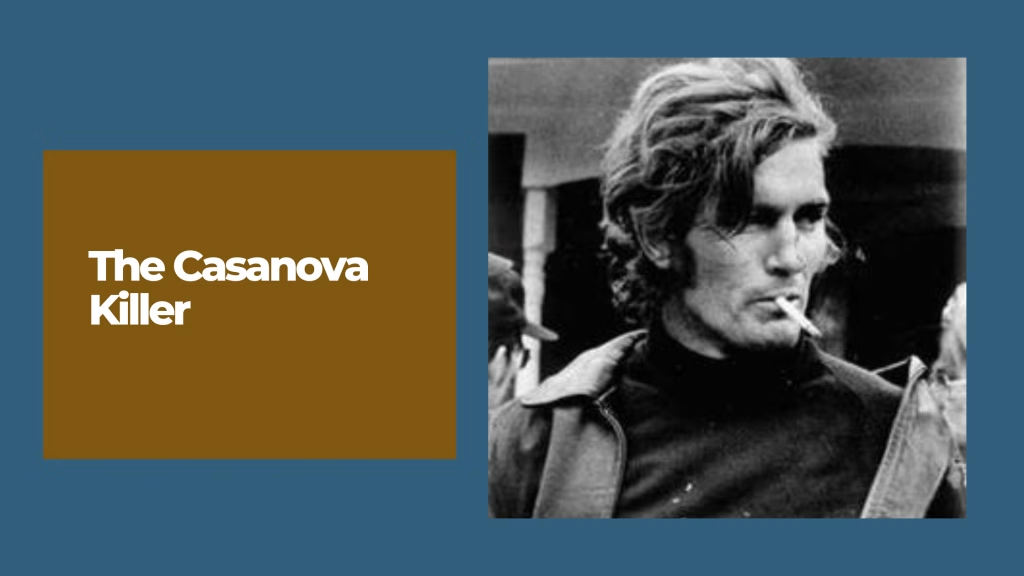

After five months of terror spanning eight states and claiming anywhere from 18 to 35 lives, the Casanova Killer’s rampage was finally over. But the story of how a charming drifter became a remorseless killer is far more disturbing than anyone could have imagined.

The Chameleon Who Killed Without Pattern

What makes Paul John Knowles stand out among serial killers isn’t just his body count. It’s his complete lack of pattern. Most serial killers have a type, a method, a signature that eventually leads to their capture. Knowles had none of that.

He killed men, women, children, and the elderly. He strangled some victims, shot others, and stabbed at least one. He raped some of his victims and left others untouched. He committed carefully planned home invasions and spontaneous murders. He was bisexual and killed both male and female romantic partners.

This unpredictability made him nearly impossible to catch. Police across multiple states were investigating murders without realizing they were hunting the same killer. By the time they connected the dots, Knowles had already moved on to his next state, his next victim, his next identity.

Early Life: The Making of a Killer

Paul John Knowles was born in 1946 in Orlando, Florida, into a troubled home. His childhood was marked by severe neglect and abuse. By age seven, he’d already had his first brush with the law for petty theft. By his teenage years, he was in and out of reform schools and juvenile detention centers.

The pattern continued into adulthood. Knowles spent most of his twenties behind bars for burglary, assault, and various other crimes. He was intelligent with an above-average IQ, but he used that intelligence for manipulation rather than legitimate success.

In 1972, while serving time in Raiford Prison in Florida, Knowles did something unexpected. He started a correspondence with a woman named Angela Covic through a pen-pal program. Angela lived in San Francisco and was drawn to Knowles’ charm through his letters. Despite never meeting him in person, she fell for him hard enough to agree to marriage.

Knowles convinced her he was a changed man, ready to leave his criminal past behind. Angela believed him. She even hired a lawyer to help secure his early release, promising authorities she would marry him and help him start fresh in California.

In May 1974, after serving his sentence, Knowles was released. He had big plans. He was going to fly to San Francisco, marry Angela, and begin his new life as a law-abiding citizen.

But Angela had other plans.

The Rejection That Triggered Everything

When Knowles called Angela from Florida to finalize their wedding plans, she delivered devastating news. She had changed her mind. The wedding was off. She didn’t want to see him again.

For Knowles, this rejection was the breaking point. In his mind, Angela represented his last chance at a normal life. Without her, there was nothing holding him back from the darkness he’d always carried inside.

Just days after that phone call, on July 26, 1974, Knowles committed his first confirmed murder. He broke into the home of 65-year-old Alice Curtis in Jacksonville, Florida. He strangled her and stole money and valuables from her home.

The killing didn’t satisfy whatever rage burned inside him. It only awakened something worse.

The First Victims: When Innocence Dies

After killing Alice Curtis, Knowles disappeared into the Florida wilderness for several days. When he emerged, he was hungry, desperate, and even more dangerous.

On August 2, 1974, he knocked on the door of a home in Atlantic Beach, Florida. When seven-year-old Mylette Anderson and her eleven-year-old sister Lillian answered, Knowles forced his way inside. The girls were family friends visiting for the day.

What happened next remains partially shrouded in mystery because their bodies were never recovered. Knowles later confessed on his “kill tapes” to murdering both girls, but some investigators doubt this confession due to a lack of evidence. The girls disappeared days before Knowles claimed to have killed them, and without bodies, the truth may never be known.

What we do know is that after this incident, Knowles began moving constantly, never staying in one place long enough to be caught.

Carswell Carr and Amanda: A Night of Horror

On November 6, 1974, Knowles met 45-year-old Carswell Carr at a gay bar in Georgia. The two men connected, and Carr invited Knowles to his home for the night.

What started as a consensual encounter turned horrific. While engaged in intimate activity, Knowles tied Carr up with a curtain cord. Carr didn’t resist, likely thinking it was part of their encounter. Then Knowles walked to the kitchen, and when he returned, everything had changed.

He had a pair of scissors in his hand and rage in his eyes.

Knowles stabbed Carr 27 times in a frenzied attack, only stopping when the scissors literally broke apart from the force. This was the first time Knowles had used stabbing as a murder method, and the brutality suggests deep emotional turmoil.

Many psychologists believe this murder was connected to Knowles’s struggle with his sexuality. He was attracted to men but deeply uncomfortable with that attraction, possibly due to societal stigma and internalized homophobia. In killing Carr, he was symbolically trying to destroy that part of himself.

But Knowles wasn’t finished. Upstairs, Carr’s 15-year-old daughter Amand was in her bedroom, unaware her father was bleeding out below. Knowles forced his way into her room, tied her to the bed, and stuffed her own stockings so far down her throat that medical examiners later struggled to remove them.

He stood there and watched the teenage girl suffocate to death. Then he raped her corpse.

After ransacking the house and stealing money, credit cards, clothes, and Carr’s identification, Knowles disappeared into the night once again.

Sandy Fawkes: The Woman Who Got Away

On November 8, 1974, Knowles checked into a Holiday Inn in Atlanta. After changing into one of Carswell Carr’s stolen suits, he went down to the hotel bar. That’s where he met Sandy Fawkes, a red-haired British journalist on assignment in the United States.

Sandy was immediately attracted to the charming stranger with unusual red hair. When he introduced himself as “Daryl Golden” and asked her to dance, she turned him down, citing work obligations. But Knowles was persistent, asking when she’d return, how long she was staying, making it clear he wanted to see her again.

Later that night, Sandy returned to the bar. This time she said yes to the dance. They went out for dinner, and during their conversation, Knowles mentioned he was heading to Miami the next day. Coincidentally, so was Sandy.

He offered to drive her. Sandy hesitated, half-jokingly telling him, “I don’t know anything about you. You could easily be another Boston Strangler for all I know.”

They both laughed at the absurd suggestion. Sandy had no idea she was actually flirting with someone far more dangerous than the Boston Strangler.

Despite her reservations, Sandy ended up going back to her hotel room with Knowles that night. The next morning, she joked, “Well, I guess you’re not another Boston Strangler. How disappointing.”

Little did she know how close to the truth her joke really was.

Six Days with a Serial Killer

For the next six days, Sandy and Knowles carried on a whirlwind romance in Miami. They went on dates, spent time together, and Sandy found herself charmed by this mysterious man who called himself Daryl.

But there were red flags. Knowles kept talking obsessively about death, saying he knew he didn’t have long to live. “I don’t know if it’s going to be two days or two months, but I know I’m going to die soon,” he told her repeatedly.

He also mentioned that his lawyer had information about him that would be released when he died, information that would make him famous. Sandy wondered if he was involved in organized crime, perhaps a drug lord or hitman. The truth was so much worse.

After six days, Sandy ended their relationship. There was no dramatic reason. She simply wasn’t feeling it anymore and wanted to move on. But Knowles didn’t take the rejection well. He seemed genuinely heartbroken, despite having only known her for less than a week.

The question that haunts this case is: why did Sandy survive? Knowles had killed for far less provocation. He’d murdered people simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Yet he never harmed Sandy, even when she rejected him.

Many believe it’s because Sandy was a journalist. Knowles was obsessed with fame and infamy. He collected newspaper clippings about his own crimes. He dreamed of being remembered as a famous outlaw. Perhaps he kept Sandy alive, hoping she would one day write about him, cementing his legacy.

She did eventually write about her experience, never knowing how lucky she was to escape with her life.

Susan MacKenzie: The One Who Almost Didn’t Escape

After Sandy ended their relationship, Knowles sought comfort with one of her journalist acquaintances, Susan MacKenzie. The next day, he offered to drive Susan to a hair appointment.

Everything seemed fine until they reached a quiet stretch of road. Without warning, Knowles pulled the car over, drew a gun, and pointed it directly at Susan’s face. He demanded sex, threatening to shoot her if she refused.

Susan somehow managed to escape the vehicle and run into the middle of the road. Knowles, not wanting to be seen chasing her down and attract more attention, simply drove away, leaving her stranded but alive.

Susan flagged down another car and went straight to the police. She described Knowles and his vehicle in detail: a red Impala. Police immediately put out alerts across Florida and surrounding states.

When officers spotted the red Impala and tried to pull Knowles over, he opened fire on them in broad daylight on a busy street. Officers dove for cover as bullets flew. By the time backup arrived, Knowles had vanished again.

But now police knew they were dealing with an armed and extremely dangerous fugitive.

Beverly Mabry and Barbara Tucker: The Home Invasion

On November 15, after ditching the red Impala, Knowles decided to commit another home invasion. But this time, he would use deception instead of brute force.

He knocked on the door of Beverly Mabry’s home, presenting himself as an IRS agent who needed to speak with her urgently. Beverly, who used a wheelchair, had no reason to doubt him. She let him inside.

The moment they entered the next room, Knowles grabbed her from her wheelchair, tied her up, and threw her in the bedroom. He gagged her with one of her own stockings, just as he’d done to previous victims.

Then he heard voices. Beverly’s young nephew was in another room, and his mother was about to arrive any minute to pick him up. Knowles quickly tied up the boy and threw him in the bedroom with his aunt.

When Barbara Tucker arrived to collect her son, she found a strange man in her sister’s house. Knowles calmly explained he was an IRS agent, but something felt wrong. When Barbara opened the bedroom door and saw her sister and son tied up and terrified, she started screaming.

Knowles grabbed Barbara, dragged her to her own car, and took her hostage.

The Journalist Who Wouldn’t Write His Story

During the drive, Barbara Tucker did everything she could to keep Knowles distracted and engaged. She asked him questions, kept him talking, anything to prevent him from deciding to kill her.

When Knowles asked what she did for a living, Barbara said she was a writer. His eyes lit up. “When all this is over, can you write a book about me?” he asked.

Knowles was obsessed with becoming famous, with being remembered. He’d told Sandy Fawkes that his lawyer had tapes that would be released when he died. He kept newspaper clippings of his own murders as souvenirs. He craved notoriety and infamy.

That night, Knowles took Barbara to a motel and tied her to the bed. He kept the television on, constantly watching for news coverage of himself. When reports about Barbara’s abduction came on, showing her missing person’s appeal, Barbara tried desperately to distract him from the screen.

His mood was unpredictable. One moment, he seemed almost friendly, as if they were companions rather than captor and hostage. The next moment, he would become violent, physically assaulting her for no apparent reason.

The next morning, Knowles simply left. He told Barbara she’d probably be found soon and walked out, leaving her tied to the bed. It took hours, but she eventually freed herself and went to the police.

She told them everything, including one crucial detail: Knowles had mentioned he was heading to Georgia.

Officer Campbell and James Meyer: The Final Victims

On November 16, highway patrol officer Eugene Campbell spotted the beige Volkswagen that Knowles had stolen from Barbara Tucker. When he pulled the vehicle over, Knowles didn’t hesitate. He drew his gun, then wrestled Campbell’s service weapon away from him.

Now armed with two guns, Knowles ordered Campbell into the back of his own patrol car and handcuffed him there. Then Knowles did something audacious. He turned on the patrol car’s siren and pulled over the next vehicle on the highway.

That car belonged to James Meyer, an innocent driver who had no idea what was about to happen. Knowles ambushed Meyer at gunpoint and forced both hostages into the back of Meyer’s car. Now he had a new getaway vehicle and two hostages.

This all happened on a busy highway in broad daylight with multiple witnesses. People called the police, but by the time officers arrived, Knowles was long gone.

The next day, police spotted Meyer’s car and pursued Knowles in a high-speed chase. The chase was so intense that Knowles lost control and crashed into a barricade. He jumped from the vehicle and fled on foot as officers shot at him. They only grazed his leg, and he managed to escape once again.

When police reached the crashed car, they found it empty except for pieces of Officer Campbell’s uniform on the back seat. There was no blood, giving them hope that the hostages might still be alive.

They weren’t. A hunter discovered both bodies the next day in a wooded area. Campbell and Meyer lay face-down in the dirt, handcuffed to a tree, each shot to death. Knowles had killed them shortly after stealing Meyer’s car.

The Manhunt

By this point, the manhunt for Paul John Knowles had become one of the largest police operations in Georgia history. Hundreds of officers were deployed. Helicopters circled overhead. Police set up roadblocks across multiple states. They had tracking dogs following his scent through fields and forests.

Tips were pouring in from the public every minute, requiring hundreds of additional officers just to man the phones at police stations.

Meanwhile, Knowles was running through fields on foot, desperate and increasingly reckless. He broke into a farmhouse, hoping to find another weapon. He found a gun and ammunition, but as he was leaving, he was spotted by David Clark.

When Knowles tried to shoot Clark and the gun jammed, it was the first time luck had truly abandoned him. Clark’s quick thinking and military training allowed him to overpower Knowles and hold him at gunpoint until police arrived.

After five months of evading capture across eight states, Paul John Knowles’ killing spree was finally over.

The Kill Tapes: A Killer’s Confessions

When police arrested Knowles, he refused to cooperate. He wouldn’t answer questions, wouldn’t provide details about his victims, and wouldn’t help investigators at all. He enjoyed the power of having information they desperately wanted.

But he did mention one thing: his lawyer, Sheldon Yavitz, had a series of confession tapes. Knowles had recorded everything, his entire killing spree, and given the tapes to his lawyer with explicit instructions not to release them until after his death.

These became known as the “kill tapes.”

Police demanded the tapes from Yavitz, but the lawyer refused. He’d made a promise to his client, and he was going to keep it. Even when police arrested him for contempt of court, Yavitz wouldn’t budge. He was willing to go to jail rather than break his word to Knowles.

Some believe Yavitz wasn’t just being loyal to his client. As a lawyer who worked with many criminals, his reputation depended on being seen as someone who would go to extreme lengths to protect his clients. What better advertisement than going to jail yourself?

Police finally broke Yavitz when they threatened to arrest his wife as well. Only then did he agree to hand over the tapes in exchange for her freedom.

The kill tapes provided crucial information about Knowles’ crimes, though he remained somewhat vague even in his confessions. Unfortunately, the tapes were later destroyed in a basement flood at the police station, so we’ll never know everything they contained.

On the tapes, Knowles initially claimed 18 victims. Days later, he changed that number to 35. To this day, we don’t know his exact victim count. Police have confirmed at least 18 murders, but the true number likely falls somewhere between 18 and 35.

The Shootout

On December 18, 1974, Knowles agreed to help police recover Officer Campbell’s service weapon, which he’d ditched in a field during his escape. Police handcuffed him and placed him in the back of a patrol car with two officers in the front: Earl Lee and Ronnie Angel.

During the drive, Officer Lee noticed Knowles had lit a cigarette in the back seat. When Lee told him to put it out, Knowles became enraged. He had somehow picked the lock on his handcuffs using a paperclip and was now free.

Read more: Patrick Kearney: The Trash Bag Killer

Knowles lunged at Officer Lee, trying to grab his service weapon. During the struggle, the gun fired twice while still in the holster. The commotion caused the driver to lose control, and the car swerved off the road and crashed.

In that moment, Officer Ronnie Angel turned around, drew his weapon, and shot Paul John Knowles three times in the chest.

Knowles slumped back in his seat, dead at age 28.

His lawyer, Sheldon Yavitz, tried to argue the shooting was unlawful since Knowles was handcuffed (not knowing he’d picked the lock). But the shooting was quickly ruled justified, and neither officer faced any consequences. Most people agreed they’d potentially saved countless future victims.

The Psychology of Chaos

What makes Paul John Knowles so fascinating and terrifying is his complete lack of pattern. Criminal profilers rely on patterns to catch serial killers. They look for victim types, preferred methods, geographical clusters, anything that can help predict the killer’s next move.

Knowles had none of that. He killed men, women, children, and elderly people. He killed strangers and people he knew. He killed for money, for sexual gratification, out of rage, and sometimes seemingly for no reason at all. He strangled, shot, stabbed, and suffocated his victims.

This randomness made him nearly impossible to catch. Police across multiple states were investigating murders without realizing they were hunting the same person.

Some experts believe Knowles simply enjoyed killing. The act itself, regardless of victim or method, gave him a sense of power and control he’d never felt in his troubled life. His childhood of abuse and neglect, combined with years in and out of prison, had created someone who felt completely disconnected from normal human empathy.

His bisexuality and apparent struggle with his sexual identity may have added another layer of internal conflict. The brutal stabbing of Carswell Carr, a man he’d been intimate with, suggests Knowles was at war with himself, projecting his self-hatred onto victims who represented parts of himself he couldn’t accept.

Where the Victims Found Peace

Unlike many serial killer cases where victims remain unidentified for years, most of Knowles’ victims were eventually identified and returned to their families. But the randomness of his selection meant that anyone could have been next.

Alice Curtis, 65, was just at home when Knowles broke in. Carswell Carr, 45, made the fatal mistake of inviting a stranger home. His daughter, Amanda, 15, was killed simply for being in the wrong house. Officer Eugene Campbell, 32, was killed doing his job. James Meyer was killed for having a car that Knowles wanted.

The tragedy is that none of these people did anything to provoke their deaths. They were simply unlucky enough to cross paths with Paul John Knowles at the wrong moment.

The Legacy of the Casanova Killer

Paul John Knowles earned his nickname “The Casanova Killer” not through any particular charm with women, but because he could effortlessly adapt to any situation. He was a chameleon who could be whoever he needed to be to get what he wanted.

To Sandy Fawkes, he was a mysterious, romantic figure. To Susan MacKenzie, he seemed like a friendly acquaintance. To Beverly Mabry, he appeared to be a legitimate IRS agent. He could be charming when he needed to be, but beneath that mask was someone capable of horrific violence at any moment.

His case remains a reminder that serial killers don’t always fit neat profiles. They don’t always have clear patterns or obvious motives. Sometimes the most dangerous predators are the ones who defy categorization, who kill without reason or warning.

What makes you think someone like Paul John Knowles could evade capture for so long? Was it his unpredictability, police limitations of the 1970s, or something else entirely? Share your thoughts in the comments below.