The date was March 13, 1977, and 17-year-old John LaMay was excited about his plans. He told his neighbor he was heading to Redondo Beach to meet someone named Dave, a guy he’d met at a gym in downtown Los Angeles. John seemed happy, looking forward to the evening ahead.

He never came home.

When John’s mother woke up the next morning to find her son’s bed empty, panic set in immediately. This wasn’t like John. He didn’t disappear for days, especially on school nights. Five days later, highway workers made a gruesome discovery south of Corona that would change everything. John’s dismembered body had been carefully washed, drained of blood, and sealed in five large trash bags. Three bags were stuffed into an empty 300-liter barrel. The other two lay beside it on the ground.

His head was never found.

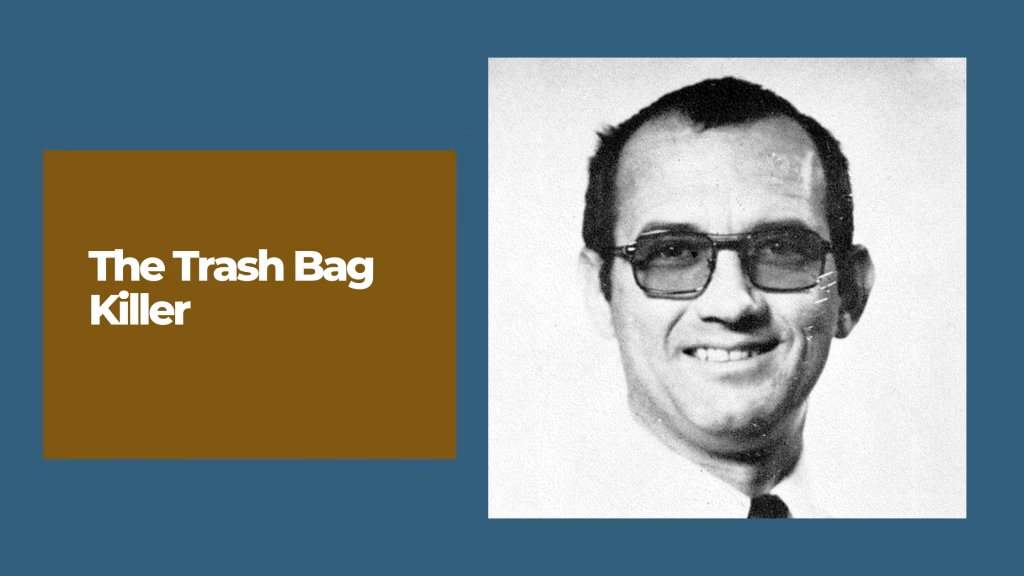

John LaMay became the final known victim in a series of murders that would haunt California for years. The killer behind these crimes was Patrick Wayne Kearney, a quiet aerospace engineer who lived an unremarkable life on the surface. But beneath that ordinary exterior lurked one of the most prolific serial killers in American history.

Who Was Patrick Kearney?

Patrick Wayne Kearney was born in Los Angeles on September 24, 1939, the eldest of three sons. Unlike many serial killers who come from broken or abusive homes, Kearney grew up in what appeared to be a stable, middle-class family. But appearances can be deceiving.

At age five, young Patrick started school in Montebello, California. Small, thin, and sickly, he became an instant target for bullies. The torment was relentless. By his teenage years, something dark had taken root in his mind. He later admitted that by age eight, he knew with absolute certainty that he would kill people someday.

The bullying followed him from school to school. In 1950, when Patrick turned 11, his family moved to the city of Rialta. New school, same story. The taunting intensified. His fantasies about murder grew more detailed, more vivid. He became withdrawn, spending hours imagining how he would kill the people who tormented him.

Then came another disturbing development. At 13, Kearney began engaging in bestiality. His father, George, may have unknowingly contributed to this when he showed his eldest son how to slaughter pigs on their property. “You shoot them in the head, right behind the left ear,” his father explained. Patrick never forgot that lesson. Years later, he would use the same method on his human victims.

The teenage Kearney actually enjoyed killing animals. He loved being surrounded by blood and gore. It gave him a sense of power he couldn’t find anywhere else in his life.

By 1957, 17-year-old Patrick graduated from high school and joined the U.S. Air Force. It was during the military service that he met David Hill, a man three years younger who would become his partner for the next two decades. For both men, it was apparently love at first sight.

The Relationship That Enabled Murder

David Hill was a towering figure at nearly 6’3″, born and raised in Lubbock, Texas. After getting kicked out of school in 1960, he joined the army but was quickly discharged with a diagnosis of “personality disorder.” He briefly married his high school sweetheart, but that relationship didn’t last.

In 1962, Hill and Kearney moved in together in Culver City, a suburb of Los Angeles. On the surface, they seemed like any other couple. Kearney worked as an engineer at Hughes Aircraft Company, eventually earning a promotion to senior researcher. Neighbors saw them as quiet, unremarkable men who kept to themselves.

Read more: The Freeway Killer (William Bonin) Lost Murder Tapes

But behind closed doors, the relationship was turbulent. Hill and Kearney fought constantly. When things got bad, Hill would disappear for days, sometimes visiting friends or his parents in Texas. Each time Hill left, Kearney’s rage built to a breaking point.

And that’s when he would go hunting.

The Killing Begins

According to Kearney’s later confessions, his first murder happened in spring 1962. He was 22 years old. He invited a 19-year-old boy to go for a motorcycle ride, took him to a deserted location, shot him in the head, and then raped his corpse. The body was never identified.

What makes this case particularly chilling is how quickly Kearney escalated. Within the same year, he killed the victim’s 16-year-old cousin, who had apparently seen his brother leaving with Kearney. Then came an 18-year-old named Mike. Same pattern: shot in the back of the head, then sexually assaulted after death.

Kearney was a necrophiliac. Like other infamous gay serial killers such as Jeffrey Dahmer and Dennis Nilsen, he was sexually attracted to corpses. The dead couldn’t reject him, couldn’t fight back, couldn’t make him feel small and powerless like the bullies of his childhood had.

In 1967, Kearney killed a man named George in San Diego, luring him back to his home. This murder marked an evolution in his methods. For the first time, he dismembered the victim in his bathtub, carefully washing each body part and draining the blood to prevent odors. He even removed the bullet from George’s head to eliminate evidence. Then he buried the dismembered body behind his garage.

After that killing, Kearney went quiet for more than a year. He was paranoid that the police would investigate George’s disappearance and trace it back to him. When no one came knocking, he realized something crucial: he could get away with murder.

The Trash Bag Method

Over time, Kearney perfected what would become his signature: the meticulous disposal of bodies in trash bags. He studied other serial killers, particularly Dean Corll, who had killed 17 young men in Houston and wrapped their bodies in garbage bags before burying them. Kearney collected newspaper clippings about Corll’s crimes, analyzing what worked and what led to his capture.

His method became disturbingly efficient. Kearney would cruise Southern California’s freeways and gay bars in his Volkswagen Beetle or van, looking for young hitchhikers or men seeking anonymous encounters. He developed a deadly routine: while driving with his left hand, he would suddenly pull out a .22 caliber pistol with his right hand and shoot his unsuspecting passenger in the back of the head.

The key was maintaining normal driving speed. He didn’t want to attract attention from other drivers who might be witnesses. After the shot, he would prop the body upright in the passenger seat and calmly drive to a secluded location.

Then came the sexual assault, followed by dismemberment. If he were at home, he’d use his bathtub, carefully cutting the body into pieces with a hacksaw. Every part was thoroughly washed and drained of blood. He left no fingerprints, no trace evidence, no mess.

Kearney would pack the body parts into large industrial trash bags, the kind he took from his workplace at Hughes Aircraft. Each bag was meticulously sealed with nylon tape. Sometimes he’d stuff multiple bags into empty oil drums. Other times, he’d scatter them across different locations: canyons, landfills, desert highways, anywhere carrion animals could destroy the evidence.

The Hunting Grounds: California’s Deadly Freeways

The 1970s were a dangerous time to be a young gay man in Southern California, though many didn’t realize it until it was too late. The AIDS epidemic hadn’t emerged yet, and a culture of sexual liberation meant gay bars, bathhouses, and anonymous encounters were commonplace. Young men hitchhiked freely, trusting strangers for rides.

They had no idea that multiple serial killers were prowling the same territories.

Randy Craft, who became known as the Scorecard Killer, picked up young men and Marines, drugged them, and subjected them to hours of sadistic torture. William Bonin, the Freeway Killer, strangled his victims and raped their corpses before dumping them roadside. The Hillside Stranglers, Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi, were abducting and murdering young women in the same area.

And then there was Patrick Kearney, quietly racking up a body count that would eventually surpass them all.

The police were overwhelmed and confused. How many killers were out there? Were some of them copycats? As bodies piled up along California’s freeways, investigators struggled to separate the cases. But gradually, they noticed distinct patterns.

One killer left victims who had been horribly tortured, often with objects inserted into their bodies. That was Randy Craft. Another strangled victim with ligatures. That was William Bonin. But one killer stood out for his meticulous approach: bodies carefully cleaned, dismembered, and packaged in trash bags.

The press dubbed these crimes the “Trash Bag Murders.” Police had a less formal name: “queer in a bag killings.”

The Victims: Young Lives Cut Short

By 1974, Kearney was killing almost monthly. His victims fit a tragic pattern: vulnerable young men, many of them gay, hitchhiking or looking for anonymous encounters. Some were runaways. Some were prostitutes trying to survive. All of them trusted the wrong person.

On June 26, 1971, Kearney picked up 13-year-old John Dechick and shot him in the head. The boy’s body was found dismembered and discarded.

Ronald Dean Smith was only five years old when he disappeared in Lennox, California, on August 24, 1974. His small body was discovered in Riverside County nearly two months later. Cause of death: strangulation. He remains Kearney’s youngest known victim.

Eight-year-old Merle Chance disappeared on April 6, 1977, while riding his bicycle near Kearney’s workplace. Kearney later admitted he strangled the boy, took his body home that night, sexually assaulted him, and disposed of the remains in Angeles National Forest. Hikers found Merle’s decomposed body six weeks later.

Albert Rivera, 21, was working as a prostitute in San Diego when Kearney picked him up on April 13, 1974. Shot in the head, raped, dismembered, and scattered. Police never recovered all his body parts.

Larry Gene Walters, 20, made the fatal mistake of accepting a ride from Kearney on October 31, 1975. His remains were found ten days later.

Seventeen-year-old Robert Bonifield was trying to fix his broken motorcycle when Kearney pulled over to offer help. The friendly stranger became his killer. Robert’s remains weren’t discovered until fall 1976.

The list goes on. Timothy Brian Ingham, 19. Mark Andrew Oreck, 20. David Allen, whose body was found on October 9, 1976. Nicholas Hernandez Jimenez, 28, who became Kearney’s oldest victim. Arthur Romas Marquez, 24, was killed in February 1977.

What’s particularly heartbreaking is how many victims remained unidentified. At least seven of Kearney’s victims were never identified. They were someone’s son, someone’s brother, someone’s friend, but they died alone and were buried as John Does.

How One Mother’s Persistence Led to Capture

Patricia LaMay refused to give up when her son John disappeared. Unlike the police, who initially dismissed it as another teenage runaway, she knew something was terribly wrong. John wasn’t the type to disappear without a word, especially during the school week.

She remembered what John’s classmate told her: he was going to meet someone named Dave in Redondo Beach. That name would prove crucial.

When John’s dismembered body was discovered on March 18, 1977, police finally took the case seriously. The name “Dave” kept appearing in their investigation, particularly on registration sheets at gay bathhouses. The trail led them to a modest home in Redondo Beach shared by 37-year-old Patrick Kearney and 34-year-old David Hill.

On March 19, investigators visited the house for the first time. Both men seemed relaxed and cooperative, even concerned about the missing teenager. They looked completely innocent. Kearney and Hill both signed affidavits stating they’d been in a relationship with John LaMay for the past two years.

When police returned on April 19 with a search warrant, they found several troubling items. Carpet fibers that matched those stuck to nylon tape were used to seal trash bags. Pubic hair samples. Dog fur. And most damning: a metal hacksaw with fresh bloodstains in the corners, despite being recently cleaned.

Laboratory analysis confirmed the worst. The fibers, hair, and blood all matched evidence found on John LaMay’s body. But the evidence, while suspicious, wasn’t quite enough for an arrest warrant. Police needed more.

When investigators returned for a third search on May 19, the house was empty. Kearney and Hill had vanished.

The Manhunt and Surrender

Kearney’s employer, Hughes Aircraft, reported that he’d picked up his last paycheck on May 20 and mailed in his resignation along with his security badge on May 26. The couple had written to Kearney’s grandmother asking her to sell their house and pay their bills.

Arrest warrants were issued for both men. When police searched the house again, they found blood residue throughout the bathroom, invisible to the naked eye but easily detected by forensic analysis. They also discovered nylon tape matching the kind used in more than 20 murders. And at Kearney’s office at Hughes Aircraft, they found the source of the trash bags.

Police knew exactly who they were looking for. Wanted posters went up across California.

On June 3, 1977, Kearney and Hill fled to El Paso, Texas. But life on the run proved impossible. The constant fear, the knowledge that their faces were everywhere, the pressure from family members begging them to turn themselves in, finally, it became too much.

On July 1, 1977, at 1:30 in the afternoon, Patrick Kearney and David Hill walked into the Riverside County Sheriff’s Office. They pointed to their own wanted poster and said simply, “This is us.”

The Confessions

What happened next shocked even experienced homicide detectives. After being advised of his rights, Kearney decided to cooperate fully with the police. On July 14, he confessed to murdering Albert Rivera, Arthur Marquez, and John LaMay.

The next day, he confessed to 25 more murders.

Kearney’s confessions were detailed and chilling. He wrote letters describing his crimes, naming victims, and marking locations on maps where bodies could be found. He explained his methods with disturbing casualness, as if discussing a hobby rather than serial murder.

The murders excited him, he told investigators. They gave him a sense of dominance he’d never felt in his bullied childhood. The idea of controlling someone completely, of holding their life in his hands, was sexually arousing in a way nothing else could match.

When detectives asked if he’d drugged victims or tortured them, Kearney looked confused. Had he inserted objects into victims’ bodies? He shook his head. “I don’t poke Venice branches,” he said flatly.

He understood that police wanted to solve as many murders as possible, but torture wasn’t his style. He seemed almost offended to be confused with Randy Craft, another freeway killer known for sadistic methods. Kearney preferred efficiency: a single bullet to the back of the head, quick and clean.

He led police to the spot behind his old Culver City home where he’d buried “George,” one of his earliest victims from 1968. Investigators dug where he indicated and found a skeleton with a single bullet hole in the skull.

Kearney described one incident that shows just how close he came to being caught multiple times. Once, while driving with trash bags full of dismembered body parts in his back seat, he got a flat tire. When he discovered the spare was also flat, he had to call a tow truck. He waited nervously as the mechanic changed the tire, certain the man would ask about the bags. The mechanic never did.

Another time, he locked his keys in the car while scouting disposal sites. With fresh trash bags full of human remains in the back seat, he spent hours trying to break into his own vehicle with a coat hanger, constantly looking over his shoulder, terrified someone would investigate.

What About David Hill?

The question that haunted investigators was: what did David Hill know?

After listening to Hill’s three-hour explanation, a Riverside County grand jury declined to indict him. Public defender Malcolm McMillan got him released under heavy security to protect him from reporters. Hill immediately fled California and returned to Lubbock, Texas.

Riverside District Attorney Byron Morton stated that the evidence against Hill was weak, and much of the information discovered actually exonerated him. Kearney insisted throughout his confessions that Hill was innocent, that he’d committed all murders alone while Hill was away from home.

But was Kearney protecting his lover? Or was Hill truly unaware that he was living with one of the most prolific serial killers in American history?

We may never know the complete truth. What we do know is that every time Hill left after a fight, Kearney’s rage needed an outlet. And he found that outlet in murder.

The Trials and Sentencing

Against his lawyer’s advice, Patrick Kearney changed his plea from not guilty to guilty. His attorney had suggested pleading not guilty by reason of insanity, but Kearney refused. Instead, he pleaded guilty to the original three murder charges and asked to be sentenced immediately.

Some speculated he was trying to avoid the death penalty, though ironically, he couldn’t have received it anyway. California’s death penalty law went into effect in August 1977, after all of Kearney’s known murders. The law couldn’t be applied retroactively.

On December 21, 1977, Superior Court Judge John Hughes sentenced Patrick Kearney to three life sentences with the possibility of parole after seven years. The judge’s words were harsh: “This defendant has definitely committed several terrible and unthinkable crimes. I can only hope that the parole board will never release Mr. Kearney. It seems that he is an insult to humanity.”

At a subsequent trial in February 1978, Kearney was charged with 18 additional murders and sentenced to 21 life terms total. He admitted guilt in each case.

If all his confessions were accurate, his true victim count includes 32 confirmed murders and possibly as many as 43. He admitted to killing two children, ages five and eight. At least four victims’ bodies were never found. Seven victims remain unidentified to this day.

The Psychology of a Serial Killer

What makes Patrick Kearney’s case psychologically fascinating isn’t just the number of victims, but the stark efficiency of his methods. Unlike sadistic killers who torture their victims, Kearney killed quickly and methodically. He wasn’t interested in prolonging suffering. He wanted control, dominance, and sexual gratification from corpses that couldn’t reject him.

Experts note that homosexual serial killers, while representing only about 5% of all serial killers, tend to show greater cruelty and are more likely to dismember victims than their heterosexual counterparts. The question of why remains complex.

Author Harold Schechter suggests that prevailing homophobia in society creates deep-rooted guilt and self-hatred in many gay men. When these feelings combine with the psychopathology of a serial killer, the result is especially terrifying. These killers often harbor intense homophobia themselves, directing their self-hatred outward onto victims who represent what they despise about themselves.

For Kearney, his victims often reminded him of the blonde, arrogant boys who had bullied him throughout childhood. In killing them, he was symbolically destroying the source of his childhood trauma, over and over again. After having sex with their corpses, he would beat them, acting out his rage against people who’d made him feel worthless.

Where Is Patrick Kearney Now?

As of 2024, 84-year-old Patrick Kearney continues serving his life sentence at Mule Creek State Prison in California. He’s spent decades behind bars, writing essays, some of which have been published. He’s been eligible for parole multiple times but has always been denied.

Los Angeles Police Homicide Sergeant Al Seth said it best: “If Kearney hadn’t been so careless, he probably would still be doing this horror.”

The Trash Bag Murders remain one of the most horrific crime series of the 20th century. In terms of confirmed victims, Kearney ranks alongside Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, and John Wayne Gacy as one of America’s most prolific serial killers.

Lessons from a Dark Chapter

The Patrick Kearney case reminds us how vulnerable marginalized communities can be to predators. In the 1970s, young gay men were easy targets. Many were runaways with no one to report them missing. Others were engaged in risky behavior like hitchhiking or anonymous sexual encounters. Society’s homophobia meant that when they disappeared, investigations often lacked urgency.

John LaMay’s mother, Patricia, was different. She refused to let her son become another statistic. Her persistence, her refusal to accept police dismissals, ultimately led to Kearney’s capture. How many lives might have been saved if she’d acted sooner? We’ll never know. But her determination ensured that the Trash Bag Killer finally faced justice.

The case also highlights how serial killers can hide in plain sight. Kearney’s boss called him a “model employee.” Neighbors knew him as quiet and unremarkable. A grocery store owner thought he was creepy because he bought so many butcher knives, but that’s hardly evidence of serial murder. Kearney didn’t fit the stereotype of a raging monster. He was methodical, organized, and terrifyingly efficient.

What aspect of Patrick Kearney’s case do you find most disturbing? Was it his cold efficiency, the sheer number of victims, or the fact that he nearly got away with it? Share your thoughts in the comments below.