On February 20th, 1926, a man calling himself Roger Wilson knocked on Clara Newman’s door in San Francisco. The 60-year-old landlady was renting out an attic apartment, and this polite stranger with a worn Bible tucked under his arm seemed like the perfect tenant.

Less than an hour later, her nephew found Clara’s body on the attic floor. She’d been beaten, strangled with such force that his fingers left deep indentations in her neck, and raped after death.

Two weeks later, it happened again. Then again. And again.

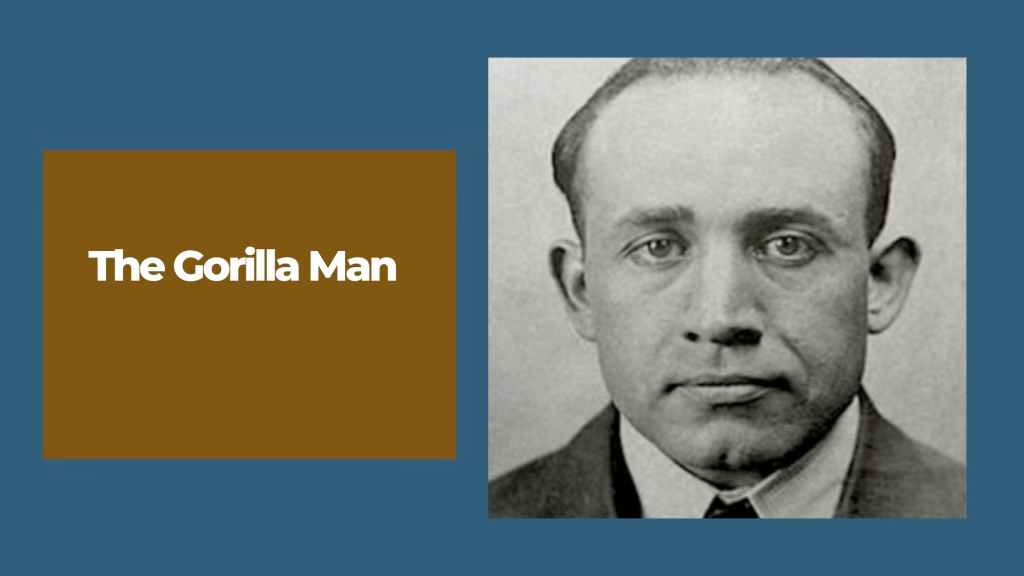

Over the next 16 months, a serial killer would terrorize landladies across North America, leaving 22 bodies in his wake. Newspapers called him the Dark Strangler and the Gorilla Man, thanks to his massive hands and peculiar features. His real name was Earle Leonard Nelson, and his story reveals how mental illness, brain injuries, and untreated disease created one of America’s most prolific serial killers.

Born into Syphilis and Madness

Earle Leonard Nelson was born on May 12th, 1897, in San Francisco. At birth, his last name was Ferrell, the same as his biological father, a Spanish immigrant who worked manual labor at the docks. His father married Earle’s mother after she became pregnant, but their marriage was neither happy nor healthy.

Both parents suffered from advanced syphilis when Earle was born. In 1897, there was no cure. Penicillin wouldn’t be discovered for decades. Syphilis was a death sentence, and both of Earle’s parents were dying from it.

Earle contracted the disease from his mother at birth. By age 13, he had both syphilis and gonorrhea. Congenital syphilis can cause devastating long-term effects: personality changes, emotional instability, intellectual impairment, and physical deformities. Larger than normal limbs. A flattened bridge of the nose. These traits, combined with his massive hands, would later earn him the nickname “Gorilla Man.”

By age two, both of Earle’s parents were dead. He went to live with his maternal grandparents, along with his aunt, Lillian, and uncle, Robert.

His grandmother was extremely religious, practicing a fundamentalist version of Christianity. She was particularly fond of the Book of Revelation, and the apocalyptic stories fascinated young Earle. That fascination would carry through the rest of his life, warping into something dark and dangerous.

The Boy Who Saw Faces on Walls

Even as a young child, Earle was different. He would sit in darkened rooms for days, depressed, then his mood would shift dramatically, and his energy would become manic. His depression sometimes manifested as self-loathing. He told his family nobody wanted him and that he’d be better off dead.

Earle would stare blankly for long periods. When he walked around, he seemed to be listening to voices that only he heard. He often came home from school missing clothing. Sometimes, even new garments would be dirty and torn into rags by day’s end.

His eating habits were bizarre. He drenched everything in copious amounts of olive oil, then ate by putting his face in the plate, slurping like an animal.

The signs of psychosis were there: extreme mood swings, odd behaviors, and hallucinations. Earle was likely suffering from both bipolar disorder and the early stages of schizophrenia, though mental health treatment in 1904 was virtually nonexistent.

At the age of seven, Earle was expelled from school. He spent class time talking to invisible people and quoting Bible passages about “the Beast.” He scared his classmates. Most stayed away from him.

Earle had violent fits and lashed out at other kids indiscriminately. When he wasn’t angry, he became withdrawn and subdued. His grandmother had no idea how to handle him. She punished him physically, but when he grew too big for that, she threatened him with religious damnation. When that didn’t work, she threatened to throw him out.

That calmed him down temporarily. But it only made his anger and feelings of helplessness worse. And Earle was only seven years old.

The Bicycle Accident That Changed Everything

In 1906, the devastating San Francisco earthquake struck, registering 8.5 on the Richter scale. Almost 500 city blocks were ruined. More than 450 lives were lost. As rumors spread of looters and armed criminals targeting women, Earle reportedly said he enjoyed the fear his female relatives expressed.

In his mind, this was the real-life effect of the Lord’s vengeance.

By age 10, Earle had earned a reputation as a troublemaker through shoplifting and unpredictable behavior. He once tried to impress older boys with a daredevil stunt that nearly killed him.

On his bicycle, Earle raced across train tracks as a trolley car roared toward him. The trolley clipped the back wheel, knocking him headfirst into the cobblestone street.

For a week, he slipped in and out of consciousness. He had wild fits of delirium when awake. On the sixth day, his fits subsided, and the doctor proclaimed him “just fine.”

The doctor was catastrophically wrong.

Traumatic brain injury victims often suffer personality changes, high anxiety, aggressive behavior, difficulty understanding social situations, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Earle was already suffering from congenital syphilis. The bicycle accident just made everything exponentially worse.

While he recuperated, his grandmother sat by his bedside and read to him. He continually asked her to reread a particular passage in Revelations about “the coming of the great Beast.” He memorized it and thought about it incessantly.

As he got older, Earle came to believe the Beast was alive and wreaking havoc in the modern world. Religious delusions are common in people with thought disorders, and Earle’s became more extreme over time.

The Voices in His Head

Earle dropped out of school at 14. He worked menial jobs but rarely kept one for more than a few weeks. At the beginning of each new job, employers were pleased with their new hire. Earle presented himself as polite and respectful. His broad chest and shoulders were perfect for physical labor.

But shortly after starting, his eccentricities would surface. Instead of completing tasks, he’d get caught staring into the distance as if watching something only he could see. Sometimes he just lay down his tools and wandered off, never to return.

His aunt Lillian remained devoted to him. After she married, she allowed Earle to stay at her home rent-free. He used his money to buy outrageous clothes for the time period: leather leggings, cowboy hats, and gaudy fake jewelry.

Despite her devotion, Lillian couldn’t ignore some of his behavior, especially around her female friends. He often let loose tirades of curse words at the dinner table and stared at visitors so intensely that they became unsettled and left. He walked around on his hands and carried chairs with his teeth.

Lillian’s friends started refusing to come to her house.

By 15, Earle was drinking heavily. Alcohol is a sedative, and many people with severe mental illnesses use it to calm down. Sometimes he’d disappear for days or weeks. He visited brothels and started fights. His sexual appetite was insatiable. His frequent use of sex workers and compulsive masturbation did nothing to ease it.

By 17, Earle’s behavior was even more difficult and unpredictable. Lillian wasn’t just worried anymore. She was terrified.

To her relief, in 1915, Earle left and traveled north on foot. Along the way, he picked up odd jobs, but his main income source was burglary. He was finally caught leaving with stolen goods when a homeowner returned. At 18, Earle was sentenced to two years at San Quentin prison.

Four Times He Joined the Military, Four Times He Failed

When Earle was released in 1917, America had joined World War I. Using his father’s last name, Ferrell, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and went to a training camp in Northern California.

Joining the military proved to be a disaster. He was quickly overwhelmed by his duties. After serving nighttime guard duty just six weeks after enlisting, Earle went AWOL.

But that wasn’t the end of his military service. He joined three more times.

Once in the Navy as a cook, he went AWOL after feeling oppressed by the chores assigned to him. Then, as a private in the medical corps, he deserted because he claimed his hemorrhoids were bothering him.

His last attempt didn’t end in desertion, but it didn’t end well either. Back in the Navy, Earle refused to work. Instead, he read the Bible and shouted about the end of the world and the coming of the great Beast. This cost him the few friends he had and led to multiple punishments.

In 1918, after weeks of complaining about headaches and refusing to leave his cot, Earle was sent to a naval hospital for psychological evaluation. Nine days after his 21st birthday, he was committed to Napa State Mental Hospital.

There, he performed well on psychological tests. The doctor who examined him concluded he was “not violent, homicidal, or destructive.”

That doctor was obviously incorrect. What was happening was that Earle, at this time, had enough self-control to fake it.

Earle escaped the mental hospital, only to be returned six weeks later. In the 13 months he spent there, he made four escape attempts. One happened the very day he’d been brought back from a previous attempt.

In May 1919, Earle ran away for the last time. The war had ended, and the Navy refused to pay for any more treatment. They formally discharged him, and the hospital didn’t bother looking for him.

The psychiatrist who treated Earle reported he was “improved and harmless.”

He was anything but.

The Marriage That Never Had a Chance

Still considered a fugitive, Earle fled to his aunt Lillian’s and assumed a new name: Evan Fuller. He found work as a janitor at a hospital, where he met a cleaning woman named Mary Teresa Martin.

Mary was 58 years old, 38 years older than Earle. She was the only other adult Mary felt comfortable around. They connected through their love of scripture.

On August 5th, 1919, Mary Teresa and Earle were married.

Mary wasn’t prepared for the behavior she encountered once they wed. His lack of personal hygiene disgusted her. His peculiar eating habits dismayed her. His clothing choices mortified her. Not only were his clothes flamboyantly mismatched, but like in childhood, he ended up with soiled and tattered clothes by day’s end.

Mary soon stopped trying to change his peculiarities. Like his aunt Lillian, she remained loyal to him.

But Earle’s behavior grew more erratic. He told Mary he was buying her a house, but tried to pay for it with just two dollars. He’d get up at 3 AM and tell Mary he was going to look for a job. She later described him as childlike, saying she was cast in the role of both his mother and his wife.

Earle’s jealousy knew no bounds. He grew angry if Mary even said hello to a stranger on the street, male or female. He hated that she was attentive to her friends, which made Mary nervous to speak to anyone, even her own family.

But it was Earle’s lust and sexual demands that Mary found most distasteful. If she refused him, he would masturbate relentlessly until she fled the bedroom. Even when she was sick, he wanted sex and forced himself on her.

Mary’s brother wanted her to leave him, especially after he discovered Earle silently conversing with the ceiling. But Mary was devoutly Roman Catholic, and divorce was forbidden.

Another Head Injury, More Hallucinations

Earle had suffered headaches since childhood, probably related to syphilis. After he and Mary wed, they became more persistent and painful. These headaches worsened after another traumatic brain injury.

Earle fell out of the upper branches of a tree and landed on his head. He received a serious concussion and a large head wound. After just two days, he fled the hospital and went home.

As the frequency of his headaches increased, his behavior became more unpredictable. He began seeing faces on walls. His religious preoccupation grew more extreme, burgeoning into a kind of mania. Earle compared himself to paintings of Christ, believing he looked just like him.

When Mary asked her priest what to do, he told her, “Kindness can cure insanity,” and she should bear with it.

The couple moved to Palo Alto, where both took jobs at the same private school. When Earle tried to pick a fight with a coworker Mary was talking with, she’d had enough. Earle insisted they were leaving. For the first time in their marriage, Mary rebelled. She told him she was staying, but he should leave.

Furious, he left but came back later that day, asking her to take him back. When she refused, he began to rage, insisting that someone or something was keeping her away from him. After telling Mary he would get her back, Earle raised his hands as if to strangle her.

She screamed and ran to a coworker’s house. They called the police.

Mary didn’t see her husband again until three months later, when she visited him in jail.

The Attack That Should Have Been a Warning

On May 19th, 1921, a man claiming to be a plumber appeared at the door of the Summers family home in San Francisco. He told the eldest son, Charles Jr., that there was a leaky gas pipe that needed fixing.

Charles immediately ushered him inside and showed him the steps to the cellar. As the plumber descended the stairs, he found Charles’s 12-year-old sister, Mary, playing with her dolls.

Suddenly, Charles heard a scream from the cellar. Racing downstairs, he discovered Mary fighting off the man, kicking and hitting him with all her might. The so-called plumber had attacked her and tried to wrestle her to the ground.

Charles pulled the man off Mary and tried holding him down, but the attacker broke free and ran from the house. Charles chased him and knocked him down several times, but the man escaped after punching Charles.

The perpetrator was caught two hours later, disheveled and bloody. He was taken to jail and booked on assault charges.

When Mary visited him in jail, she was shocked by his appearance. After threatening suicide and plucking out his eyebrows with his fingernails, police found him in a straitjacket, secured to the bed. He was extremely agitated and screamed about faces on the wall mocking him.

At this point, Earle was experiencing both visual and auditory hallucinations. And let me tell you something about those hallucinations: they’re never nice. The faces weren’t complimenting him. The voices weren’t supportive. They were punishing, abusive, and frightening.

To avoid jail for the assault, his wife and aunt had him committed once again to the same hospital. The doctor who once claimed Earle was fine amended his statement, declaring him “a constitutional psychopath with outbreaks of psychosis.”

Earle remained at the facility for two years and four months, after which he escaped and went to his sister. But he scared Lillian so much that she turned him away, giving him money and food, then called the police.

Two days later, Earle was sent back to the hospital, where he remained for 16 more months. Despite his suicidal threats, the hospital released him on March 10th, 1925, noting: “discharged as improved.”

Although Earle persuaded Mary to come back to him, he soon took off and made his way to Northern California.

That’s when he began to kill.

The Landlady Killer

At approximately 1:30 PM on February 20th, 1926, Earle, introducing himself as Roger Wilson, knocked on Clara Newman’s door. He was responding to the room-for-rent sign posted in the window of her San Francisco boarding house.

As Clara led him upstairs to show him the attic apartment, they passed her nephew on the second-floor landing. The nephew noticed the visitor’s olive complexion, short stature, broad chest, and large hands. He also saw the well-worn Bible he carried.

Less than an hour later, the nephew saw the man again as he was leaving. The stranger told him, “Tell the landlady I’ll be back to take the room.”

When Clara didn’t come downstairs, her nephew went looking for her. He discovered her body on the attic floor.

Clara was nude with ligature marks on her neck and large indentations from the killer’s fingers and fingernails. She’d been badly beaten. The coroner determined she’d been raped after death, a fact not revealed to the public at the time.

Less than two weeks later, on March 2nd, 1926, the body of 65-year-old Laura Beal was discovered by her husband in a vacant apartment they owned. She’d been strangled with the silk belt from her dress. Her husband assumed she’d been showing the apartment to a potential lodger when she was attacked.

An autopsy confirmed she was also raped after her death.

These two cases began a 16-month pattern of murder and post-mortem rape carried out by Earle Leonard Nelson.

Why Landladies?

Between 1926 and 1927, Earle was linked to 22 murders. The majority of his victims were female and over 50.

You’re probably wondering: what’s with all the landladies? Did he have some kind of fetish?

The answer is simpler and more chilling. What does a landlady do when she wants to rent out a room? She opens the door to a stranger and lets them into her home.

There are only two factors necessary for most male serial killers: the victim has to be female, and she has to be “getable.”

In Earle Nelson’s time, women who rented out rooms met both criteria.

On June 10th, Earle killed another landlady who was on her way out when he showed up and inquired about a room. This victim put up a fight. Her autopsy revealed nine fractured ribs, indicating he used his body weight to hold her down while strangling her. She, too, was sexually assaulted after death.

After three similar murders, police had eyewitness descriptions. Newspapers started referring to the killer as the Dark Strangler and the Gorilla Killer, based on descriptions of his large hands and strange features.

A Trail of Bodies Up the West Coast

For the next few months, Earle murdered women, primarily landladies up and down the West Coast. One in Santa Barbara. One in Oakland. Three in Portland, Oregon.

The women were brutalized, strangled, and then raped.

Police in Oregon were initially skeptical that their victims were connected to the Dark Strangler because the bodies had been hidden: one behind a furnace, one in the attic, one in a trunk. The Dark Strangler hadn’t done this before.

But they soon recognized the similarities and joined the hunt.

After Portland, Earle returned to San Francisco, where he murdered his ninth victim, a 66-year-old landlady. The very next day, he varied from his usual victim choice and attacked a pregnant woman in her home in Burlingame, California.

She was able to fight him off and call for help. Neighbors chased Earle into the street, where he escaped. But finally, police had an accurate, detailed description.

Within days, Earle found his next victim in Seattle, Washington: a 48-year-old widow selling her house. She was found strangled and badly beaten in the basement. The autopsy revealed her cause of death may have been a heart attack during the beating.

This time, there was no sexual assault, but she’d been robbed of thousands of dollars’ worth of jewelry sewn into her underwear.

Crossing the Country

A month later, he was in Council Bluffs, Iowa, where he murdered a 40-year-old woman. The next three victims were in Kansas City, Missouri. Two were landladies, but much younger than the others, both in their 20s. Earle also strangled to death one woman’s eight-month-old son.

Then he traveled to Philadelphia, where he killed a 60-year-old woman. Then Buffalo, where he beat and strangled a 35-year-old.

Two days after the Buffalo murder, on June 1st, 1927, he strangled two women in Detroit, Michigan. Two days after that, he was in Chicago, where he murdered a 32-year-old woman.

Police across the United States were now posting public warnings and looking for the killer. With so much scrutiny, Earle decided to leave the country.

Read more: The Vitebsk Strangler: Gennady Mikhasevich

A man reported to police that he’d picked up Earle in Minnesota and given him a ride to the Canadian border. Earle entered Winnipeg, Canada, on June 8th, 1927.

He wasted no time resuming his murderous behavior.

The Canadian Victims

The next day, he encountered a 14-year-old girl selling paper flowers on the street in Winnipeg. She was never seen alive again.

On June 10th, Earle murdered a 27-year-old landlady with a hammer. Police in Winnipeg quickly surmised the Dark Strangler had crossed the border. They immediately began searching local boarding houses.

They came across a boarding house where Earle had rented a room. There, they discovered the body of the 14-year-old girl stuffed under the bed.

By June 13th, Winnipeg police were offering a $1,500 reward for information leading to the Dark Strangler’s capture.

Earle left and traveled back roads to escape notice. On June 15th, he reached the small town of Wakopa. He entered the town’s general store, where the owner recognized him and telephoned the police.

An officer arrived and arrested Earle, who said his name was Virgil Wilson. The officer placed him in a cell, removed his shoes, and handcuffed him to the bars.

When the officer left to call Winnipeg police, Earle removed a nail from the cell and used it to pick the locks. He escaped and fled to the train station, hiding in a grain elevator while waiting for a train.

The next day, he took a chance and walked to the station. Railway passengers recognized him and alerted a train official, who detained him.

Ironically, when the train arrived, it was carrying dozens of Winnipeg law enforcement officers who’d come to look for him.

The Trial and Execution

Even after arrest, Earle maintained his name was Virgil Wilson. He was booked at the Winnipeg police station, photographed, and fingerprinted.

Canadian police sent the photographs and fingerprints to stations across Canada and the United States. Several witnesses confirmed this was the same man they’d encountered during murders in the U.S. Then, San Francisco police matched the fingerprints.

The Dark Strangler had finally been caught.

During his preliminary hearing on June 27th, he was charged with two murders. Earle told the judge that murder was not possible for a man of his high Christian ideals. He pleaded not guilty.

He was also indicted for murders in San Francisco, Portland, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Buffalo.

Throughout the trial, newspapers reported that Earle showed “complete indifference.” He sat in the prisoner’s dock with his head thrown back and his eyes closed.

Earle’s attorney asked for clemency because of his insanity. Among the 60 witnesses, only two testified for the defense: his aunt and his wife, who hoped for a not guilty by reason of insanity verdict.

The trial lasted five days. On Saturday, November 5th, 1927, the jury deliberated for only 48 minutes before finding him guilty of murder. He was sentenced to death by hanging.

Before the trap door beneath his feet was sprung, he told spectators: “I am innocent. I stand innocent before God and man. I forgive those who have wronged me and ask forgiveness for those I have injured. God have mercy.”

God may have had mercy, but the justice system did not.

Earle Leonard Nelson was executed in Winnipeg, Canada, on January 13th, 1928. He was 30 years old.

Understanding the Monster

In most of Earle’s murders, he strangled his victims, then raped them post-mortem. This is necrophilia, an abnormal sexual desire primarily seen in men who murder specifically to defile their victim’s corpse.

As Earle’s victim count grew, his need to murder climbed. He’d commit the homicide, then the need would taper off for weeks. The FBI later termed this an “emotional cooling-off period,” which became a determining factor when judging killers as serial killers.

But during his murder rages, he no longer just targeted older women. He victimized any female who was “getable.” As the law closed in, the risk of being discovered only seemed to excite him more.

Earle couldn’t stop himself. And it doesn’t appear he wanted to.

The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities

Looking back at Earle Leonard Nelson’s life, the failures are staggering. He was born with syphilis, a disease that damaged his brain before he could walk. He suffered at least two traumatic brain injuries that worsened his condition. He showed clear signs of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder from early childhood.

He was committed to mental hospitals multiple times. Each time, doctors declared him “improved” or “harmless.” Each time, they were catastrophically wrong.

The 12-year-old girl he attacked in 1921 survived only because her brother was home. That should have been the moment authorities recognized the danger. Instead, they released him four years later.

By the time he started killing in 1926, Earle was a walking time bomb of untreated mental illness, brain damage, and sexual compulsion. Twenty-two women paid for society’s failure to properly treat or contain him.

The victims deserve to be remembered: Clara Newman, 60. Laura Beal, 65. A 14-year-old girl is selling paper flowers in Winnipeg. An eight-month-old baby in Kansas City. And 18 others whose names have faded from memory.

They were mothers, grandmothers, daughters, widows, trying to make ends meet by renting rooms. They opened their doors to a polite stranger with a Bible, never suspecting the monster behind his eyes.

What disturbs you most about this case: the system’s repeated failures to properly treat Earle’s mental illness, or the 22 lives that might have been saved? Share your thoughts below.