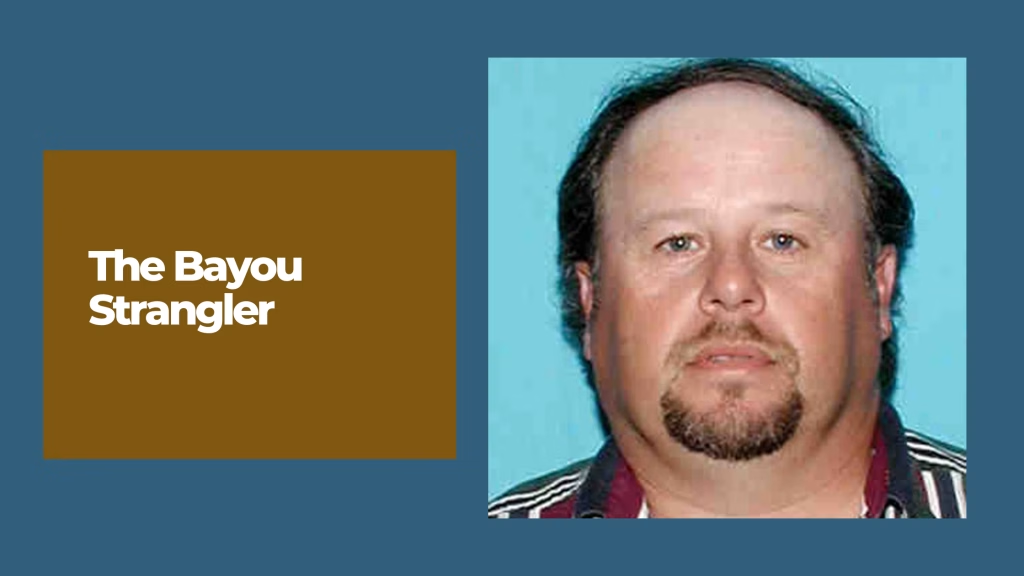

On December 1, 2006, police arrested a short, stocky man at a homeless shelter in Houma, Louisiana. His name was Ronald Dominique, and he’d been under surveillance for nearly a year.

When detectives brought him in for questioning, Ronald said he wanted to cooperate. They started by asking about Oliver LeBanks, a 21-year-old whose body had been found under an overpass in 1998.

Ronald explained that he’d met Oliver in the French Quarter. They’d gone to his car and had sex. Then, Ronald claimed, Oliver pulled out a knife and tried to rob him. He said he panicked, hit Oliver with a tire iron, and choked him to death with a seatbelt.

What about the other victims?

Ronald eventually confessed to 23 murders spanning nearly a decade. Most victims were young Black men, many with criminal records, most involved in sex work or drugs. They were people society had forgotten about.

For years, while bodies kept appearing in ditches and cane fields across southern Louisiana, authorities struggled to connect the cases. Different parishes, different detectives, minimal evidence. Some deaths were ruled accidents or overdoses without proper investigation.

The victims were considered disposable. Drug addicts. Criminals. Sex workers. People nobody cared about.

That attitude allowed Ronald Dominique to kill for nine years before finally being caught. This is the story of the Bayou Strangler and the invisible victims he targeted.

The Outcast Who Never Fit In

Ronald Dominique was born on January 9, 1964, in Thibodaux, Louisiana. Thibodaux is a small community about 60 miles west of New Orleans. His parents were low-income laborers who had one daughter, Lanie, before Ronald was born.

He grew up as an oddball who didn’t have an easy time making friends. As a child, his interest in the glee club got him labeled as gay. In a conservative religious state like Louisiana, especially in the 1970s, that label made you unlikely to make friends.

The truth was, Ronald actually was gay. But he wasn’t going to come out of the closet while in school.

Once Ronald became a young adult, he decided to open up about his sexuality and started participating in the local gay scene in New Orleans. Unfortunately, he didn’t find it any easier to make friends there than he did in school.

He was still seen as an oddball. Most people just didn’t feel entirely comfortable with him.

Ronald began attending Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, studying computer science, but he didn’t last long. He dropped out in the early 1980s.

On June 12, 1985, when Ronald was 21 years old, he was arrested for telephone harassment. Apparently, making prank phone calls was more fun than college. Ronald was caught sexually harassing someone over the phone. He was given a $75 fine.

Ronald tried to get by with low-wage labor jobs, but he was frequently fired. He spent most of his young adult life living with his mother or his sister.

Without a steady job or much of a social life, Ronald would have to find a new way to meet his sexual needs.

The First Attacks

In 1993, Ronald met a young drifter and told him he could sell him some marijuana. A few days later, the man arrived at Ronald’s house. Ronald told him he didn’t want him to see where he hid his stash and asked him to wait in the bathroom.

When Ronald announced he was ready, the man came out of the bathroom to see a gun instead of a bag of weed. Ronald handcuffed the man and raped him.

When he was done, he ordered the man to leave. The victim went straight to the police.

The police didn’t take him seriously. They wrote a report, filed it, and forgot about it.

In August 1996, Ronald had another man file a rape charge against him. This time, neighbors saw the victim climb out of a window at Ronald’s residence. He told them he’d been raped.

Since there were witnesses, authorities couldn’t ignore the report. Ronald was arrested. His bail was set at $100,000, so Ronald had to wait in jail for his trial to begin.

While in jail, Ronald claimed he was physically abused by other inmates. He said he was gang-raped, which led to him needing stitches in his rectum.

It was during this time that Ronald swore he would never go back to jail. He decided he needed to kill his victims after raping them so they couldn’t report him.

In November, the prosecutor was unable to locate the man who’d filed charges against Ronald. The case was dismissed.

Ronald immediately claimed he’d been falsely accused. He began resenting the legal system for how he was treated.

He’d escaped prison time. Now he knew he needed to make sure no more victims could go to the police.

The First Murder: David Mitchell

On July 13, 1997, 19-year-old David Mitchell attended a birthday party at a family member’s house. After the party, David went to a local bar where he was lured outside by Ronald.

Ronald raped and strangled David. He dumped his body on the side of River Road in Hahnville, right near his own residence in Boutte.

When David failed to show up for work on Monday, his family knew something was wrong. David loved his job at St. Charles Parish Hospital.

When the family heard that a young Black man fitting David’s description was found on the side of the highway, they were afraid it was him. When the news showed a picture of the dead man’s face on screen, David’s sister screamed.

That’s how they found out David was dead.

Detectives investigated the scene and questioned the family, but they were left with zero evidence.

Ronald kept quiet for five months before his urge to kill returned.

The Pattern Emerges

His second victim was 20-year-old Gary Pierre, who’d been recently released from prison on drug charges. His body was discovered on December 14, 1997, on Vickers Lane in Montz. Gary had been raped and strangled.

Seven months later, on July 31, 1998, 38-year-old Larry Ranson was found along Highway 3160 in Hahnville. He’d also been raped and strangled.

Ronald seemed to always have a cooling-off period. He would space out his attacks by months, which helped keep earlier crimes below the radar.

It appeared Ronald preferred young Black men, but he was willing to hunt outside those parameters. Larry Ranson was 38, older than most victims. Ronald would also have five white victims throughout his killing spree.

Oliver LeBanks and the First Real Evidence

On October 3, 1998, Ronald went to a small gay bar in Marrero called the Rawhide. He struck up a conversation with 21-year-old Oliver LeBanks.

Oliver was open about turning to sex work when he needed extra money. He was young, attractive, and knew he could get the work. When he offered his services to Ronald, the short, stocky man accepted and suggested they go to his car.

They’d agreed on $30 cash for oral sex. Once at Ronald’s vehicle, Oliver began performing when the man became forceful. Ronald flipped him onto his stomach and raped him.

After he finished, Ronald grabbed a tire iron and swung it at Oliver’s head. With Oliver unconscious, Ronald put a belt around his neck and strangled him to death.

Ronald found a secluded overpass where he dragged Oliver’s body out of the car. He dragged him completely under the overpass before getting back in his car and leaving.

This was the fourth Black man to be raped and strangled in relatively proximity to each other. It was clear that a serial killer was active in the area.

The first three victims gave zero evidence. No hairs, no prints, no fibers, no DNA.

Oliver would be different. When his body was autopsied, hairs were collected and sent to the lab for DNA testing. But there was no other evidence to connect them to anyone.

The Killing Accelerates

Ronald hadn’t taken a cooling-off period after Oliver’s murder. In mid-October, he met 16-year-old Joseph Brown and bought crack cocaine from him. Then he invited the boy into his car to smoke it with him.

After they finished smoking, Ronald beat Joseph on the head with a blunt object and strangled him with a plastic bag. He dumped his body in the nearby town of Kenner.

A month later, on November 27, 18-year-old Bruce Williams went into the French Quarter in New Orleans and disappeared. His body was dumped in an industrial area in Jefferson Parish.

The three killings within a short period must have satisfied Ronald because he went quiet for another six months.

By this time, Ronald was working as a laborer at the St. Charles Parish Maintenance Department. After his break, he was ready to kill again.

At the end of May 1999, Ronald met 21-year-old Manuel Reed. His body was found on May 30 in a dumpster behind a business in Kenner. He’d been raped and strangled.

A month later, Ronald raped and strangled 21-year-old Angel Mejia. His body was discovered in front of a dumpster in an industrial area on June 30.

The Shoeless Killer Urban Legend

Around this time, local news began reporting that bodies of men without shoes were likely connected. This is how Ronald Dominique became associated with an urban legend about the “shoeless killer.”

It was true that some of Ronald’s victims were discovered without shoes, but those shoes were usually nearby. Most likely because Ronald found some victims at gay clubs, they may have been willing participants in sex at first, and removed their shoes themselves. It’s also possible that shoes got kicked off during struggles.

Other victims were found with their shoes still on, so this detail wasn’t part of a serial killer’s pattern. It was just sensationalized reporting.

Detective Thornton’s Lonely Investigation

Thirty-four-year-old Mitchell Johnson’s body was found on September 1, 1999, under the same overpass where Oliver LeBanks’s body had been found.

Detective Dennis Thornton of the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office was assigned to the case from the beginning. He knew he was tracking a serial killer and couldn’t believe how either brazen or sloppy the killer was.

The killer clearly didn’t care if his victims were found. He’d dumped a second body just feet away from a previous victim.

The most frustrating part was that he wasn’t leaving any evidence behind at dump sites. Not a clue outside of a few hairs, and those were worthless unless they had something to compare them to.

There were nine bodies in, and they didn’t have a clue who the suspect might be.

Detective Thornton finally got a break when locals said they saw a white male in his mid-30s with a receding hairline cruising the same area where Mitchell had disappeared. Now, at least they had a description of a possible suspect.

They made a sketch based on the description. Local news published it, but it didn’t get them any leads.

Either the picture scared Ronal,d or it was a coincidence, but in November 1999, he quit his job and towed his trailer home from Boutte to the city of Houma. He parked it at his sister Lanie’s house, got a labor job, and kept his head down.

This allowed him to easily remain under the radar of authorities.

Two Years of Silence

Ronald likely wanted to take a break from killing to let the heat die down. But the urge got to him one more time.

Twenty-three-year-old Michael Vincent disappeared on New Year’s Eve after meeting Ronald. Ronald would later say they fooled around for a bit, but Michael wanted to stop. When Ronald kept going, Michael threatened to call the cops, which made him a liability.

On January 1, 2000, Michael’s body was found propped against a barbed-wire fence. The autopsy revealed no evidence that would help the case.

Since Ronald had completely dropped out of sight, he spent almost two years resisting his urges. He got a second job as a delivery driver for Domino’s Pizza and stayed quiet.

Well, mostly. In May 2000, he got into a fight with a woman in public. Bystanders called the police. He was arrested for disturbing the peace, pleaded guilty, and paid a fine.

Not a smart move for someone trying to fly below the radar.

This didn’t stop him from getting into another altercation on February 10, 2002. While Ronald was attending a Mardi Gras festival in Houma, a woman bumped into a stroller with her car, waking up a sleeping baby.

Ronald was enraged and demanded that the woman apologize, which she did. Then Ronald slapped her across the face. Police arrived and arrested him for assault.

Again, not knowing the truth about the perpetrator, he was put into a work release program, which he completed in October 2002.

What Happened to the Killer?

During the two years Ronald was inactive, Detective Thornton could only wonder what was going on. Had the killer moved out of state? Had he died? Was he still killing but hiding the bodies?

It was possible the killer could get away with 10 murders if he just stopped. At the time, the BTK killer had killed the same number of people between 1974 and 1991, then seemingly vanished. He was eventually caught in 2005.

Authorities were clueless about the cause of the lull in activity. But Detective Thornton didn’t give up. He searched the news and police records to see if any other murders elsewhere could be connected to the serial killer.

Ronald knew he would have to return to killing. It was something he needed to do.

The New Strategy

Ronald used his job as a pizza delivery driver to study the area. He found a secluded spot to move his mobile home. His brother-in-law got him permission to park the trailer on the property of the Dixie Shipyard, a large secluded area.

He decided he needed a new plan to get young men into his car without a struggle. Once they were in his car, he’d be able to do whatever he wanted.

The plan was simple: show straight men a picture of an attractive woman and tell them she wanted to have sex with them. But she only did it if they were tied up first.

For gay men or those willing to have sex with him, he’d claim he was afraid of being raped and needed them tied up for his own safety.

It was disturbingly effective.

Kenneth Randolph Jr. lived only a few miles from Ronald in August 2002. At 19 years old, Kenneth had already been arrested three times for having sex with someone underage. He’d been spared serious time and was serving eight months of probation when he met Ronald.

Kenneth was found lying face down in a cane field on October 6, 2002. The body was completely nude except for a pair of white socks.

Since this was a different jurisdiction, LaFourche Parish Sheriff’s Detective Tom Atkins was assigned the case. Fingerprints led to Kenneth’s identity.

It was only a few days before Ronald found his next victim. He seemed to be making up for lost time during his long break.

Noka Jones and the Detectives Connect the Cases

On October 12, Shelley Weston got off work, went grocery shopping, and returned home, where she lived with her boyfriend, Noka Jones. She said Noka helped her put away groceries before he got on his bike and rode down the street to buy cigarettes.

While riding back, Ronald pulled up next to him and made some sort of proposition that would earn Noka money.

Shelley said Noka returned home, brought his bicycle inside (it was his main transportation and he didn’t want it stolen), then told her he was going back outside to smoke. This was what he said when he was going out to do things.

Eventually, she went to bed, not worried that her boyfriend hadn’t returned.

The next morning, a patrol officer spotted a young Black man lying motionless near an overpass in Boutte. He checked for a pulse, found none, and called it in.

Detective James Deslatte arrived on the scene. He knew nothing about a possible serial killer in the area. As far as he knew, this was a single case.

An autopsy revealed Noka had been raped and strangled. Detective Deslatte began looking for who could have committed the crime. He found out Noka had dealt drugs for a couple of people who might have had reason to kill him, but the rape threw off that theory.

Because Detective Thornton was diligently looking for other cases that matched the 10 he already had, when he saw reports of Kenneth Randolph and Noka Jones, he met with the other detectives to compare notes.

It seemed that if Detective Thornton wasn’t dead set on stopping a serial killer, nobody would have cared that young Black men were dying in Louisiana.

There were no national reports of a serial killer in the area. Local news had covered it, but when they offered the story to the national press, they weren’t interested.

Most other authorities would chalk these deaths up to young Black men, many with criminal records, who didn’t deserve that much attention.

The Victims Nobody Cared About

One of these men was 19-year-old Darrell Woods, who had a record of petty theft. He’d just been released from jail a few months earlier and was living at his mother’s house.

On a sunny day in late May 2003, Darrell left with a friend to hang out and retrieve his bike. A few days later, Darrell’s body was found by a couple of young men riding dirt bikes near a cane field.

The heat had caused the body to start decomposing quickly. After fingerprints were run, authorities knew it was Darrell. They were familiar with him and his family.

The coroner found his cause of death to be asphyxia, which initially led investigators to believe it may have been an accident since Darrell suffered from asthma.

Darrell’s bike was found near the body. Detectives noted there was no dirt on the wheels and no tire tracks. The bottoms of Darrell’s feet were clean, which meant it was a dump job.

Eventually, the murder was linked to the others. But it didn’t bring them any closer to catching the serial killer.

Read more: The Machete Killer: Juan Vallejo Corona

The Drug Addict Whose Death Was Called an Overdose

On October 10, 2004, Tropical Storm Matthew was pounding the Gulf Coast in southern Louisiana. The storm caused over $300,000 in damage.

Ronald went out looking for another victim that evening when he met 46-year-old Larry Matthews. Larry was a drug addict who didn’t have a stable place to live.

Ronald saw him walking down the street, hitchhiking, trying to make it out of town due to the storm. When Ronald offered to bring him back to his house so they could do drugs together, Larry wasn’t going to pass that up.

Larry hopped in Ronald’s car. They went to the trailer and did drugs. At some point, Larry did too much cocaine and went unconscious. Ronald took the opportunity to rape and strangle him.

Larry’s body was discovered near a pond in Des Allemands between Houma and Boutte. Even though the body had no socks or shoes, had linear abrasions on each buttock, and vascular hemorrhaging, the coroner ruled the cause of death to be accidental drug overdose based on a toxicology report.

Again, this was a case of “eh, it’s a drug addict, so we’ll just phone it in.”

They got his identity from fingerprints, but found no evidence that would help when he was later connected to the other cases.

The Task Force Finally Forms

Detective Thornton wanted to put together a task force that would bring multiple agencies together so they could more efficiently work to catch a serial killer who was building up a serious body count.

Unfortunately, a task force would cost money. As long as the victims were criminals, drug addicts, and prostitutes, the money couldn’t be justified.

By 2005, the number of victims was rising at an alarming rate. The state finally agreed to assemble a task force.

It was at the first task force meeting that Detective Thornton met Detective Don Berseron. The two would become the key investigators on the case.

Bodies continued appearing:

- July 2: Alonzo Hogan, 28, was found in a cane field

- August 16: Wayne Smith, 17, was found in a ditch

Detective Berseron realized that three or four victims had been picked up from the Sugar Bowl Motel, a low-cost motel many sex workers used.

This was as much progress as they made before one of the most destructive hurricanes hit the area.

Hurricane Katrina Slows Everything Down

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Mississippi, causing 1,836 fatalities and $125 billion in damage.

This seriously slowed the investigation. The area around New Orleans was destroyed. There was no electricity, no fresh water. People were homeless and struggling to survive.

Fortunately for people in Houma, the damage wasn’t as bad. They were able to recover more quickly.

One of those people who recovered quickly was Ronald Dominique. As soon as the storm subsided, Ronald found another victim.

Forty-year-old Chris Deville was the brother of a local police officer. He’d been hitchhiking when Ronald picked him up. His body was dumped in a field where it remained for more than a month.

When he was finally discovered, his flesh had been eaten by rodents. All that was left was a skeleton, but an ID was found nearby.

This would be the only one of the serial killer’s victims who had a stable background.

The Break in the Case

When detectives were able to get back to work in November 2005, they came up with a plan. They decided to talk to recent parolees to see if any had unusual interactions with anyone.

The killer seemed to commonly pick up people with criminal records. Maybe some parolees had interacted with the killer but hadn’t taken him up on whatever he was offering.

When they talked to a man named Ricky Wallace, he told them about a strange encounter. He was walking down the street when a chubby white man in a black GMC Sonoma pickup truck pulled up next to him and asked if he wanted a beer.

Then the man held up a picture of an attractive woman and asked if he wanted to have sex with her. The driver said she really liked having sex with guys like him.

Though the idea was far-fetched, Ricky wasn’t going to miss out on sex with a beautiful woman. He got in the truck.

As they were driving, the man started telling him that the woman preferred to have men hogtied before she had sex with them. When they got to their destination, Ricky would need to be tied up.

Once they walked into the man’s trailer home, Ricky started noticing gay porn magazines around. He finally realized the offer was too good to be true.

He turned around, walked out the door, and walked away from the trailer. The man did nothing to stop him.

Finally, a Suspect

The investigators were thrilled when Ricky said he remembered exactly where the trailer was and agreed to take them there.

When they arrived at the location, they saw a trailer home parked at a house on Bayou Blue Road across the street from a church.

Detective Berseron opened the mailbox and pulled out a piece of mail. It was addressed to Ronald Dominique.

They finally had a suspect.

That was all he was at this point. They didn’t have evidence tying him to the crimes. Their best option was to bring him in and ask questions.

When detectives went back to his trailer and asked him to come in for questioning, Ronald nonchalantly agreed.

He was an enigma to the investigators. Did he think he could outsmart them? Or did he just not care about the outcome, just like leaving bodies out in the open?

They spoke to him about Ricky’s claim. Ronald admitted he’d picked Ricky up and taken him to his trailer, but he claimed it was consensual. When Ricky became uncomfortable, he left.

Technically, Ronald hadn’t done anything illegal.

Then they told him they were working on cases of young men being picked up and killed. They requested a DNA sample to rule him out.

At this stage, Ronald had to volunteer his DNA because they didn’t have enough evidence for a warrant. He hesitated but then said, “I have nothing to hide,” and agreed.

Ronald was likely confident since he didn’t think he’d left DNA behind. He used condoms when raping victims. But there can sometimes be leakage, and the coroner was able to collect trace amounts of semen on a couple of bodies.

There were also hairs collected from one victim.

Detectives sent the samples to the lab for comparison. For now, they had no option but to let Ronald go.

One More Murder Under Their Noses

The interview didn’t scare the killer into laying low.

On November 5, 2005, Ronald was at work reading meters when he met 21-year-old Nicholas Pellegrin. Nick was doing work on his house. Ronald approached and asked if he was interested in making extra money later.

Nick agreed but said he needed to finish what he was doing. Ronald came back a few hours later and picked up the young man.

They went back to his trailer, where Nick was raped and strangled. Nick’s body was found on November 9 in a wooded area in the neighboring parish.

Detectives Thornton and Berseron were enraged that Ronald would brazenly murder another young man right under their noses.

They racked their brains trying to find a way to bring him in. But they didn’t have evidence to hold him on.

A few days later, they got the DNA results back. They were a mitochondrial match to Ronald.

This was good news because it gave them a link that would allow them to get warrants. But it couldn’t definitively prove he was the killer.

A nuclear DNA match would identify an individual. A mitochondrial DNA match just proved it was either Ronald or a close family member.

It was technically possible that the killer was someone related to Ronald. His sister, maybe?

The killer was obviously Ronald, but the DNA could still create reasonable doubt in court.

The Surveillance

For this reason, they decided to put Ronald under constant surveillance and try to get stronger evidence. They didn’t want to allow Ronald to kill again, so they kept an eye on him all the time.

Investigators matched every victim to the locations Ronald was living and working at those times. They fit together perfectly.

They also got more DNA results from other victims, but they, too, were mitochondrial DNA.

Authorities made it almost a full year keeping Ronald from killing.

But in October 2006, he was able to shake the patrol car that was tailing him. He found his final victim in Houma.

Twenty-seven-year-old Christopher Sutterfield’s body was discovered on the side of Highway 69 on October 15. Ronald had dumped the body in Iberville Parish, at least an hour from Houma. This was the farthest he’d ever gone to dump a body.

The body was located soon after, and the task force was notified right away. Ronald’s attempt at slowing down the investigation didn’t work.

The coroner took swabs from Christopher’s body and sent them to the lab, hoping for a stronger match. They didn’t get anything.

Not willing to risk letting Ronald kill again, they rolled the dice and got a warrant to arrest him based on the DNA they had.

The Arrest and Confession

By this time, Ronald had moved out of his trailer and was staying in a homeless shelter. He would later claim he knew he was going to be arrested and didn’t want to create problems for his sister and brother-in-law.

Ronald Dominique was arrested on December 1, 2006.

When he was taken in for interrogation, he said he wanted to cooperate with detectives.

They started by talking about Oliver LeBanks because that case had DNA and was one of the two victims listed on the warrant.

Ronald explained that he met Oliver in the French Quarter. They went to his car and had sex. Then, Ronald claimed, Oliver pulled out a knife and tried to rob him. He said he panicked, hit him with a tire iron, and choked him to death with a seatbelt. Then he dumped the body because he didn’t want to go to jail.

A self-defense claim was not uncommon when someone finally got caught for murder.

The detectives moved on to Manuel Reed, the other victim on the warrant. Ronald explained that he met Manuel outside a bar and agreed to have sex with him in his car.

Once there, Manuel held him down and forced himself inside Ronald. Ronald told a story about having had surgery on his rectum, so he couldn’t have anal sex. He told Manuel that, but Manuel forced himself on him anyway.

That’s when Ronald grabbed the tire iron and hit him on the head. Then he strangled him to death with a rope and dumped the body.

Ronald eventually confessed to all 23 murders. He explained that most of the men agreed to being tied up because he told them he was afraid of being raped.

That was how he was able to secure young men who were all clearly in better physical shape than he was.

If the men were straight, he’d show them a picture of an attractive woman and claim she wanted to have sex with them. But she’d only do it if they were tied up.

Many of Ronald’s stories claimed the sex was consensual, but afterward the victim demanded more money or threatened to go to the cops. He said that would cause him to panic and kill them.

It’s possible, but he claimed it happened almost every time.

Justice for the Forgotten

Ronald was eventually charged with eight of the murders. But his conviction would hinge on his cooperation since there was no solid physical evidence linking him to any of the crimes.

The district attorney offered to take the death penalty off the table if he pleaded guilty to all eight counts. Ronald agreed.

On January 2, 2007, Ronald took authorities on an all-day road trip around the area and pointed out all 23 dump sites.

Ronald tried to tell a sob story about how he was accused of rape and put in jail, but he’d proven he was innocent and gotten out. While inside on this “phony rape charge,” he himself was raped and turned into an angry person.

Of course, that’s not true. The charges were dropped because the victim took off. Ronald had never proven his innocence. He simply got lucky.

In 2008, Ronald Dominique was sentenced to eight consecutive life sentences. He will never be released from prison.

The Victims Who Deserved Better

Twenty-three men lost their lives to Ronald Dominique’s violence between 1997 and 2006:

- David Mitchell, 19

- Gary Pierre, 20

- Larry Ranson, 38

- Oliver LeBanks, 21

- Joseph Brown, 16

- Bruce Williams, 18

- Manuel Reed, 21

- Angel Mejia, 21

- Mitchell Johnson, 34

- Michael Vincent, 23

- Kenneth Randolph Jr., 19

- Noka Jones (age unknown)

- Darrell Woods, 19

- Larry Matthews, 46

- Michael Barnett (age unknown)

- Leon Lett (age unknown)

- August Watkins, 31

- Kurt Cunningham, 23

- Alonzo Hogan, 28

- Wayne Smith, 17

- Chris Deville, 40

- Nicholas Pellegrin, 21

- Christopher Sutterfield, 27

These weren’t just statistics. They were sons, brothers, boyfriends, and friends. Many were struggling with addiction or poverty. Some were involved in sex work to survive. Some had criminal records.

Society decided they were disposable. Their deaths didn’t matter enough for proper investigations. Their cases were dismissed as accidents or overdoses. Their murders went unconnected for years because different parishes didn’t communicate.

If Detective Dennis Thornton hadn’t been so determined to catch this killer, Ronald Dominique might still be free today.

The Lessons We Still Haven’t Learned

The case of Ronald Dominique reveals disturbing truths about how we value human life.

When victims are poor, Black, gay, involved in drugs or sex work, or have criminal records, their deaths are treated differently. Investigations are less thorough. Cases are dismissed more easily. Media coverage is minimal or nonexistent.

Ronald Dominique specifically targeted people he knew society wouldn’t miss. He was right.

It took nine years to catch him. During that time, he killed 23 people. Multiple survivors reported him to the police, and nothing was done. Different parishes investigated similar murders without connecting them. DNA evidence sat unprocessed. The national media wasn’t interested in the story.

More than 50 years after the civil rights movement, we still have a two-tiered system of justice. Some victims matter more than others.

The 23 men Ronald Dominique murdered mattered. They deserved better investigations. They deserved justice sooner. They deserved to be seen as human beings whose lives had value.

Ronald Dominique is in prison, where he belongs. But the systemic failures that allowed him to operate for nearly a decade continue to this day.

Pingback: List of serial killers in the United States - Serial Killers Perspectives